This is the second post in a series of posts about a phenomenon in American politics called (by me) the "polarization paradox". You can read about what exactly that is, some examples of it in recent politics, and its six root causes here.

Today, most political outcomes - namely, how voters and politicians behave 90% of the time - are more predictable than they've ever been. Yet, the outcomes of the few political and policy decisions that matter the most - the protection of basic rights, the renewal of crucial poverty alleviation programs, the choice of human being to briefly become the most powerful person in the universe - are highly idiosyncratic and unpredictable. There are six primary causes spanning the psychological to the institutional to the fundamentally epistemic for why this is the way things are, in my view.

But before we spend our time getting into those, it's worth asking: why is this paradoxical state of our politics actually bad (and not just confusing)?

For starters, it means that government isn't deliberately and thoughtfully by the "will of the many", but rather hastily shaped in tense, bursty windows by the "whims of the few". It may even be shaped by the absence of the few: the death of a single senator may mean a complete dead halt in a sitting administration's ability to nominate judges; the death of a single Supreme Court justice may be responsible for upending long-held rights like abortion access in our society. This is highly undemocratic and - for lack of a more sophisticated vocabulary - kind of insane.

I want to get a little more specific though and touch on why the polarization paradox is uniquely bad for each of three significant groups1 in the American political system: the shapers, the observers, and the recipients.

Why it’s bad for the “shapers” of politics

Who I call the shapers, political scientists (anachronistically, in my opinion) dub 'elites’: active participants in the political process who have clearly defined policy agendas. They are our elected officials, our Greta Thunberg’s, our Joe Biden’s; they are also your Boomer neighbors who show up to town hall meetings to protest up-zoning; they are our Tucker Carlsons and even our Elon Musks. There are at least two reasons why the sudden chaos produced by the polarization paradox is bad for them.

Niche interests have outsized influence

The tense, concentrated chaos generated by the polarization paradox is bad for most shapers because it forces them to cater to niche, rather than broad interests, ultimately distorting their policy goals to begin with. If all it takes is a small group of dedicated activists or even a single person to derail your agenda ... you either change your agenda or you get wrecked.

The current fast-track, jam-it-all-in-there model of Congressional legislation via budget reconciliation is maybe the perfect example of this. Rather than putting individual bills through a "long, long journey" of "patience and courage" a la Schoolhouse Rock, members of Congress will jump through all sorts of procedural loopholes to tack on their preferred policy onto the federal budget resolution that must pass each year. There's a clear incentive for this: budget resolutions need a simple majority of 51 votes in the Senate to pass rather than the usual 60 votes to overcome the filibuster. But in return this introduces so many more elements of chaos. It forces lawmakers to both draft up lots of complex legal provisions across totally disparate different issues, but also make sure said provisions look like 'budgetary' adjustments so they can actually pass under reconciliation. Budget reconciliation only happens once a year, so it has to happen before that deadline. Oh, and given the 50-49 Democrat-Republican composition in the Senate, a single person from the majority party can derail the whole agenda.

So less Schoolhouse Rock, more Schoolhouse Acid Remix at 3x speed.

Bad guesswork has consequences

There's another big reason why the polarization paradox is bad for shapers. When these kinds of tense, unpredictable political showdowns go down, not only does it force shapers to cater to a minority of voices, but it forces a lot of guesswork about what that minority wants. This is maybe less true in the example of law-making on Capitol Hill; even though we're the ones guessing about what obstructionists like Joe Manchin or Kirsten Sinema want, it's precisely the job of party leadership to unambiguously figure out what they want. But guesswork basically describes how elected representatives try to understand what their constituents want.

And this guesswork is not great. There's a lot of good research on the "conservative bias" in politicians' perceptions of their constituents. This unsurprisingly arises in Republican members of Congress (though even if their districts or states are not that conservative) and even long-time incumbent Democrats whose staffers have outsized relationships with business interest groups. On the other hand, some firsthand accounts from the progressive consulting world suggest Democrats have the opposite 'liberal college kid bias' and are out of touch with what working-class voters want.

In either case, poorly extrapolating what your constituents makes political life for you, as a shaper, more unpredictable since it's never clear whether you're truly being 'responsive' enough to the right people to win re-election. It also means that in the eleventh hour when you need to make a decision, you'll end up doing things that are out of step with your constituents - like opposing a popular child welfare program when your constituents have one of the highest child poverty rates in the country - further exacerbating chaos and unpredictability in our politics.

Why it’s bad for the “observers” of politics

Next up, we have the group that I call the observers of politics, who are a very different beast from the shapers. By far the largest of the three groups, these people range from the mostly-uninformed, not-very-online Ordinary Hardworking Americans who are occasionally exposed to Fox News talking points over water-cooler conversation to the armchair political hobbyists who are highly tuned in to the latest Trump scandal but couldn't tell you where they're registered to vote.

Importantly, the observers will take it upon themselves to participate by voting, marching, and signing, but only when the vibes are right. The vibes created by the polarization paradox are, unfortunately, not those vibes for two possible reasons.

Unpredictability causes anxiety

This is sort of a tautological statement - anxiety stems from uncertainty which is synonymous with 'not being able to predict things'. And anxiety may not necessarily be a 'bad thing' (for democracy). There's a good number of polls and even causal evidence (though mostly from experiments) suggesting that anxiety motivates voters to turn out, especially in recent years. This alone would actually have a "thermostatic effect" on the polarization paradox, by broadening the size of the electorate and making election outcomes less contingent on the whims of small groups.

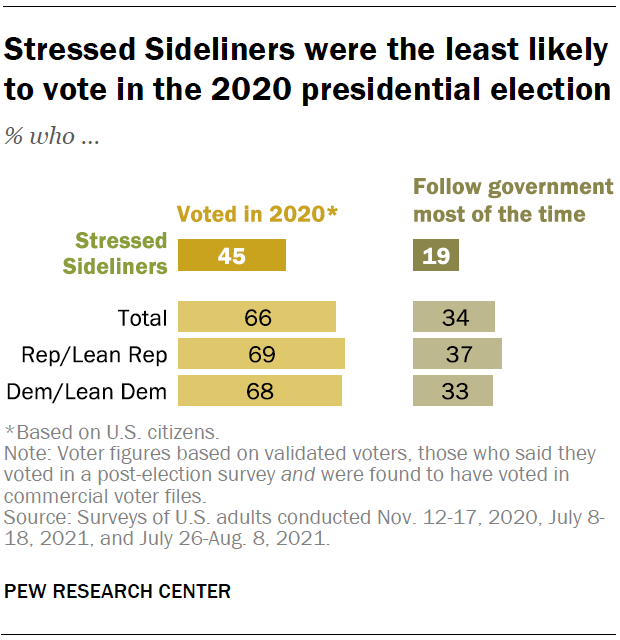

But for observers, who are less likely to participate in politics to begin with, anxiety may very well have the opposite effect and depress their turnout. There actually isn't a ton of evidence on what anxiety does to this crucial hinge group in elections, so we can't say this for sure, but the picture probably isn't good. In some related findings, Pew Research Center polls have identified a group of Americans called the ‘stressed sideliners’ who make up at least 15% of the public, and are both stressed and anxious about public affairs but are largely disconnected from politics and unwilling to participate.

Unpredictability, more generally, breeds cynicism

Even if anxiety doesn't depress observers' political engagement, cynicism can - or at least affect how observers engage with politics. According to literally every poll that has ever asked about it in the past two decades, there is no shortage of cynicism about the political process in America.

The recent saga of the narrowly averted government shutdown gives some clues as to what prolonged this cynicism can do. Peter Barker from the New York Times points out that despite the dire consequences of a sustained shutdown, there's disproportionately little attention (as captured by Google search trends) being paid by the public. Nor has there been any measurable response in financial markets, compared to the weeks before the 2013 or 2018-19 shutdowns. And so numb are Americans to this kind of dysfunction, that according to some insiders, there's been shockingly few calls or emails from constituents to their representatives complaining about the shutdown.

Thus the cycle of the polarization paradox continues as the ‘observers’ grow increasingly cynical and fail to join the ranks of ‘shapers’, giving room to louder, more ideological ‘shapers’ in the process, which further perpetuated and normalizes the arm-flailing, fire-alarm-pulling (both metaphorical and literal) dysfunction on Capitol Hill.

Why it's (especially) bad for the “recipients” of politics

Lastly, and most importantly, I want to talk about the recipients of politics and policy. You might argue that all of us sidewalk-walking, park-going, public-goods-consuming people are technically recipients of politics, but I'm talking about the most acute benefactors of public policy, whose basic survival hinges on the particular qualifications and provisions of public services.2

Unpredictable politics is bad for all of those folks we've talked about, but it’s deeply stressful and harmful to this group, above all. The most salient example of such harm is the expiration or rollback of pandemic-era benefits - expanded SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) allotments, unemployment benefits, and child tax credit payments, to name some of the big ones - forcing families to suddenly confront impossible trade-offs between things like paying rent and putting food on the table. “A life in limbo” is a common phrase that ‘recipients’ use to describe the unreliability of American social policy.

At the end of the day life can be deeply unpredictable. The role of government, one would argue, should be to reduce this unpredictability. It can’t be when the politics that shapes government is also unpredictable. While some kind of social safety net is strictly better than nothing, a safety net that only works half the time is uniquely terrible.

For whomst doth chaos bring benefit?

There are many people who have a strong incentive for politics to be unpredictable. Recruitment for liberal activist groups, for example, spiked after Trump's election — Trump's election was perversely one of the best things to happen to progressive activism in recent years. Ordinary people who engage in hostile online political interactions are often motivated by a psychological “need to perpetuate chaos” against a perceived status quo or dominant order; seeing examples of others burning down the house only fuels this fire.

The two current wrecking balls of American politics, Joe Manchin and Kirsten Sinema, benefit immensely from legislating unpredictably. Shapers who are in the rare position of being ‘pivot votes’ stand to gain enormously from lobbyists whose main job is to make them more predictable through the exchange of knowledge, connections, jobs, … and straight up money (via fundraisers and donations).

Finally, the existence and operation of a profitable political media ecosystem rests on the premise that politics is a chaotic, unpredictable, but also exciting mess. The Trump presidency, once again, arguably provided life support to all the cable news networks, whose dwindling audiences would likely have dwindled faster in the absence of said chaos.

But isn’t predictable politics also bad?

You might ask: if politics becomes too predictable, isn’t that also bad? What if our political system was predictably bad and there’s no disruption of that system? (As was the case in most of the American South for much of the 20th Century when Southern Democrats ruled with a terrible iron fist3 with virtually no competition from national Republicans).

I totally agree.

I think that politics should be more predictable, not that there shouldn’t be a menu of political ideas that are publicly put on trial for voters to select from. In fact, amongst the six root causes of the polarization paradox (spoiler alert) I think that competitive parties and slim majorities between factions is not something we should get rid of for reasons to come in a future post.

I do think, though - on behalf of ‘shapers’, ‘observers’, and ‘recipients’ alike - we should do something about those other five pesky root causes of the polarization paradox.

Stay tuned for more on those.

Not necessarily mutually exclusive and definitely not exhaustive. And yes, these are just terms I made up to illustrate a point in a slightly less boring way.

One again, important to emphasize the first footnote here: even so-called ‘recipients’ have agency in the political system. See the phenomenon well-studied in political science called policy feedback, where (in my parlance) recipients rapidly mobilize to become shapers in order to defend their programs and services (e.g. Social Security) from proposed threats.

Different from today's Democratic Party!!