The polarization paradox

Most political outcomes in our polarized era are extremely predictable. Yet politics today deeply feels like a chaotic unpredictable mess. Which story is true?

When I tell people I'm a political scientist, pretty much the only follow-up question I get asked - if I don't just get a blank stare or a polite nod or some other insinuation that that's not a real job - is something along the lines of: can you please explain why politics is so chaotic?

There’s a growing theory of American political behavior that I think offers a good answer to this question and it's got a cool name: partisan calcification. The remainder of this post will be a graceful articulation of an answer to this question for cocktail parties past and future (yours and mine).

Partisan calcification isn't just a theory that accurately describes the past decade of American politics, but an active prediction of the next few years, if not decades, of politics in America. This is also not my theory, so I’ll let the theorizers — maverick political scientists Lynn Vavreck, John Sides, and Chris Tausanovitch — explain in their own words.

Voters are increasingly tied to their political loyalties and values. They have become less likely to change their basic political evaluations or vote for the other party’s candidate. This is not just polarization but calcification. And just as it does in the body, calcification produces rigidity in our politics — even when dramatic events suggest the potential for big changes.

In this world, the party affiliation next to a candidate’s name trumps every other consideration at the ballot box: political experience (what we call “valence” attributes), particular policy positions, possible red flags such as an insatiable taste for human flesh, etc etc.

But does this Treehouse of Horror truly describe the world we live in?

Partisan calcification in action

To be fair, we have seen the partisan polarization of our modern era coming. The idea that partisanship is the basis for most political behavior dates back to the 1960s. What's different today is the sheer extent of calcified, insatiable-taste-for-human-flesh-ignoring partisanship.

To take an example: major economic crises loomed large over Jimmy Carter in the 1980 elections and Barack Obama in the 2012 elections.

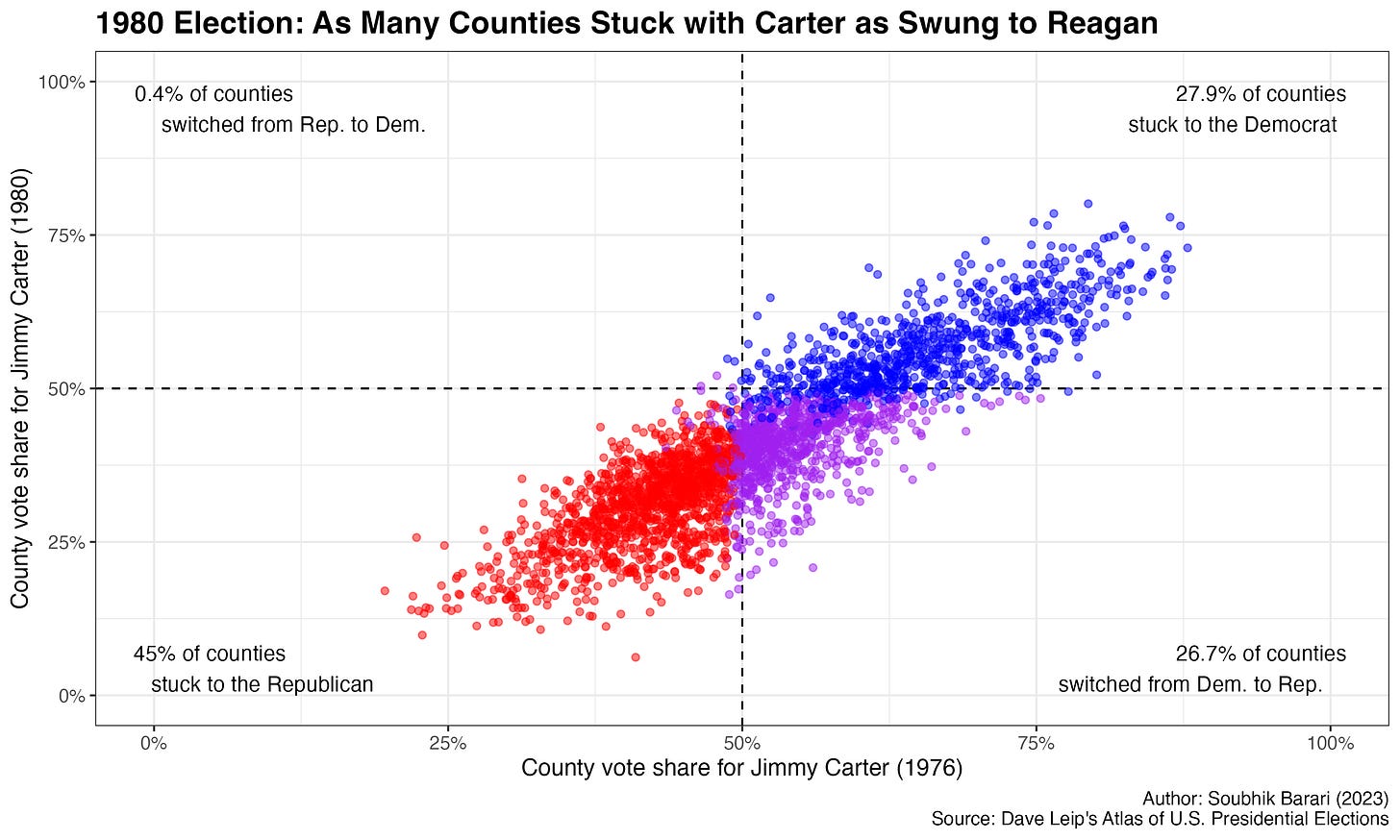

In 1980, about 26% of Carter-won counties in 1976 were won by Reagan in 1980 - the same as the percentage of counties that stayed the course with Carter in 1980.

Fast forward to 2012 where only 7% of Obama-won counties in 2008 were won by Romney in 2012.

In short, economic crisis was able to change minds about one President and not so much the other.1 As the mavericks put it: “rigidity, even when dramatic events suggest the potential for big changes”. In aggregate, calcification means predictability: the correlation in county-level presidential vote share across consecutive years of elections has approached something like 0.97. This is bonkers because human behaviors rarely, if ever exhibit correlations anywhere close to 0.97. (*a loud bell thematically tolls in the distance*)

But there's a flip side to this phenomenon: national elections are basically decided by the mood swings of a tiny number of voters. If you're a consultant for a presidential candidate and you're divvying up your campaign resources across the map, less than 10% of counties in the U.S. are "fluid" enough in their partisan majorities to be, bluntly speaking, worth seriously campaigning in.

Here's, for example, the measly 60 counties that flipped in their partisan direction between the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections that are plausibly up for grabs for either party:

This is a dramatic shrink from even 2016 where roughly 7% of counties (a small number but still more than 3 times as many) swung from Obama-winning to Trump-winning:

So let this sink in: whether your preferred presidential candidate wins or loses basically comes down to (1) which direction a double-digit number of counties will go and (2) whether the counties that are typically predictable in their vote split will for, some reason we probably won’t identify until after the election, over- or under-perform this time around. A paragon of stable politics, this is not.

Now, you might think there are more voters who identify as independents than ever that are up for grabs, but most of them (i) are closet partisans and (ii) live in safely blue or red states where, thanks to the Electoral College, their votes quite plainly do not matter.

The paradox, explained

These portraits of American politics seem at odds with each other, but they're both simultaneously true, painting a deeply annoying paradox of contemporary politics: today, most political outcomes are more predictable than they've ever been, and yet the few political outcomes that seem to matter are highly idiosyncratic, unpredictable, and are decided by the “whims of the few” rather than the “will of the many”.

This paradox doesn’t just describe of voters, but also the behavior of elites. These days, most members of Congress are shockingly predictable in how they vote on most issues, most of the time, especially the members of the incumbent President's party (yep, including the most defiant members!).

Yet, month after month, the Biden administration has seen one unpredictable legislative show-down after another: passage of the Inflation Reduction Act; attempted passage of the Build Back Better Plan; debates over filibuster reform; the federal codification of abortion rights, and the list goes on. And every time, the entire country anxiously waits to hear what the same two wrecking-balls are going to say as they step out of the deal-making room.

How did we get in this mess and how do we get out?

A politics that is both observably stable but quintessentially chaotic was not supposed to be the result of more polarization in our politics.

In fact, a special committee of eminent political scientists in 1950 famously called for more polarization (read: differentiation) between the two parties precisely in order to create more political stability. Evidently, the parties did what I did in all of grad school and skimmed the abstract of the paper and skipped the details - specifically the recommendations accompanying greater ideological differentiation. But even if they hadn't, there are a number of things about our politics that the mid-century tweed-coats didn't see coming.

In my view, our polarization paradox can be broken down into -- bear with me, gracious reader -- six major root causes. Over the next several weeks and months on Somewhat Unlikely, we will explore each one in greater detail.

The first two have to do with the current equilibrium or “resting state” of voters and politicians today:

Natural diversity in human beings’ political preferences.

Competitive parties, each with their particular electoral edge.

The third has to do with a design element of American political institutions that (so warned the 1950 special committee) make policy outcomes especially unpredictable:

Winner-takes-all systems of aggregating voters’ and politicians’ preferences into outcomes.

The next two have to do with our elections specifically, the parts where ordinary plebes like you and I probably “feel” the most chaos in our politics:

Candidate-centric elections (as compared to party-centric elections).

Media incentives for more chaos in our politics.

And, finally, a fundamental feature of Politics that will never change:

The inherent un-observability of democratic politics.

There are other features of our politics, of course, that contribute to the paradox2, but to me, these are the fundamental six features. If we could solve any of one of these, our politics would feel a great deal less chaotic.

But why does making politics less chaotic even matter? Surely, there are more important things - inequality, poverty, mobility, crime, health - that we should spend our time and energy fixing about America? And even if it does matter, how do we get there?

Stay tuned for part 2, where I'll make a case for both of these things.

This is not to claim that public opinion changed rationally as Presidents tend to have less power over the economy than voters believe. There are also, of course, many other confounding differences between Carter and Obama, but since this is Substack and not my American politics seminar from grad school, I’m pulling back on the “well, actually”’s.

A key factor that I've left out from this list is anti-majoritarianism, i.e. systems that produce outcomes that agree with only a tiny majority or an outright minority of actors.

An example of this is the “first-past-the-post” rule of presidential primaries where candidates need only receive most rather than the majority of votes to win.

While I think there are gains from making voting systems, both electoral and legislative, more super-majoritarian (e.g. ranked-choice voting, instant runoff, supermajority rules in Congress), there are also clear costs and burdens that come with these systems that may increase, rather than decrease instability in our politics. Moreover, so long as factors (1) and (2) hold in my list of six, super-majoritarian systems may simply have a dilatory rather than chaos-reducing effect on our political outcomes: just look at the filibuster.