Secular countries, not just developed ones, use AI more

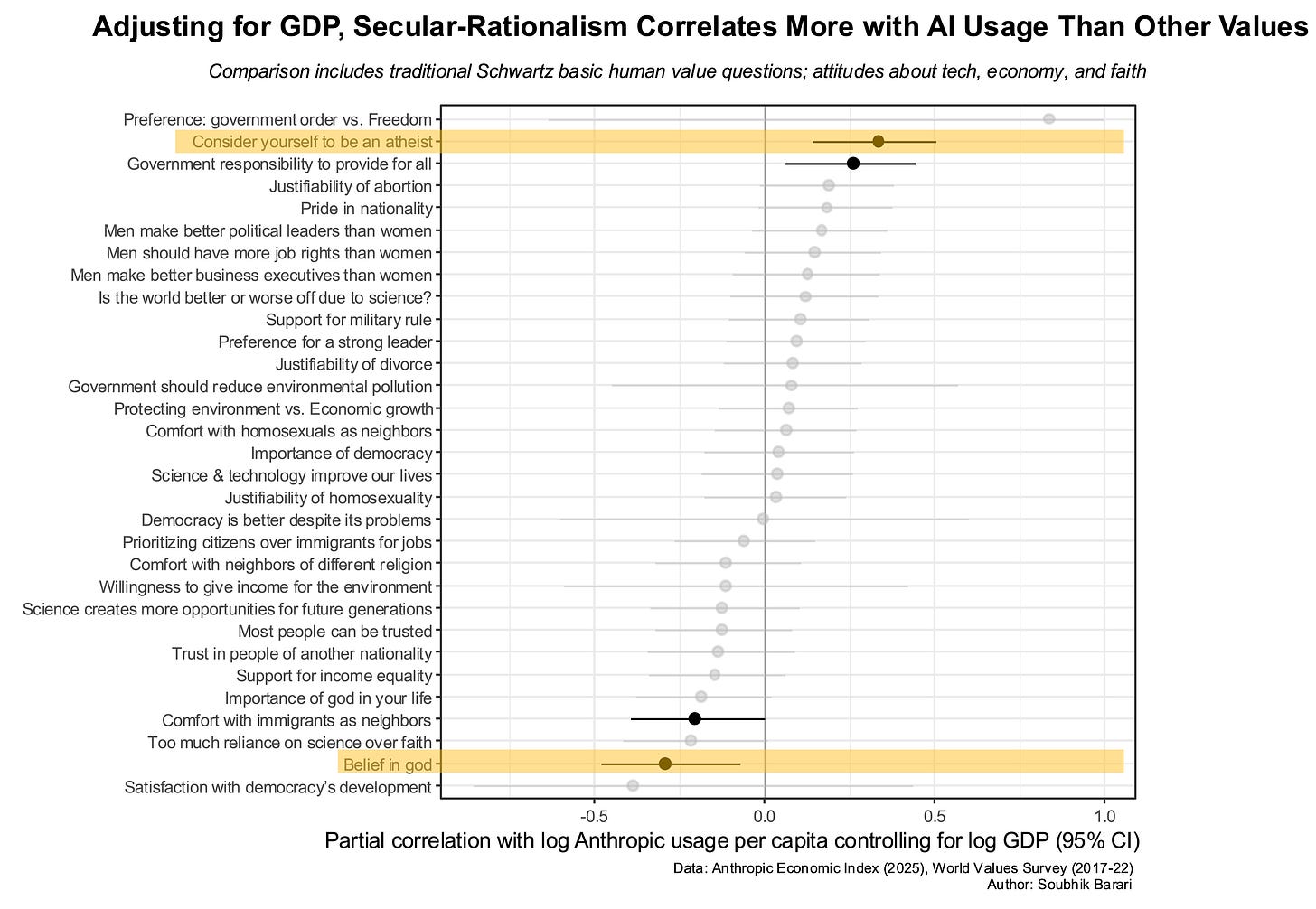

Controlling for GDP, secular-rationalism predicts AI usage more than other values

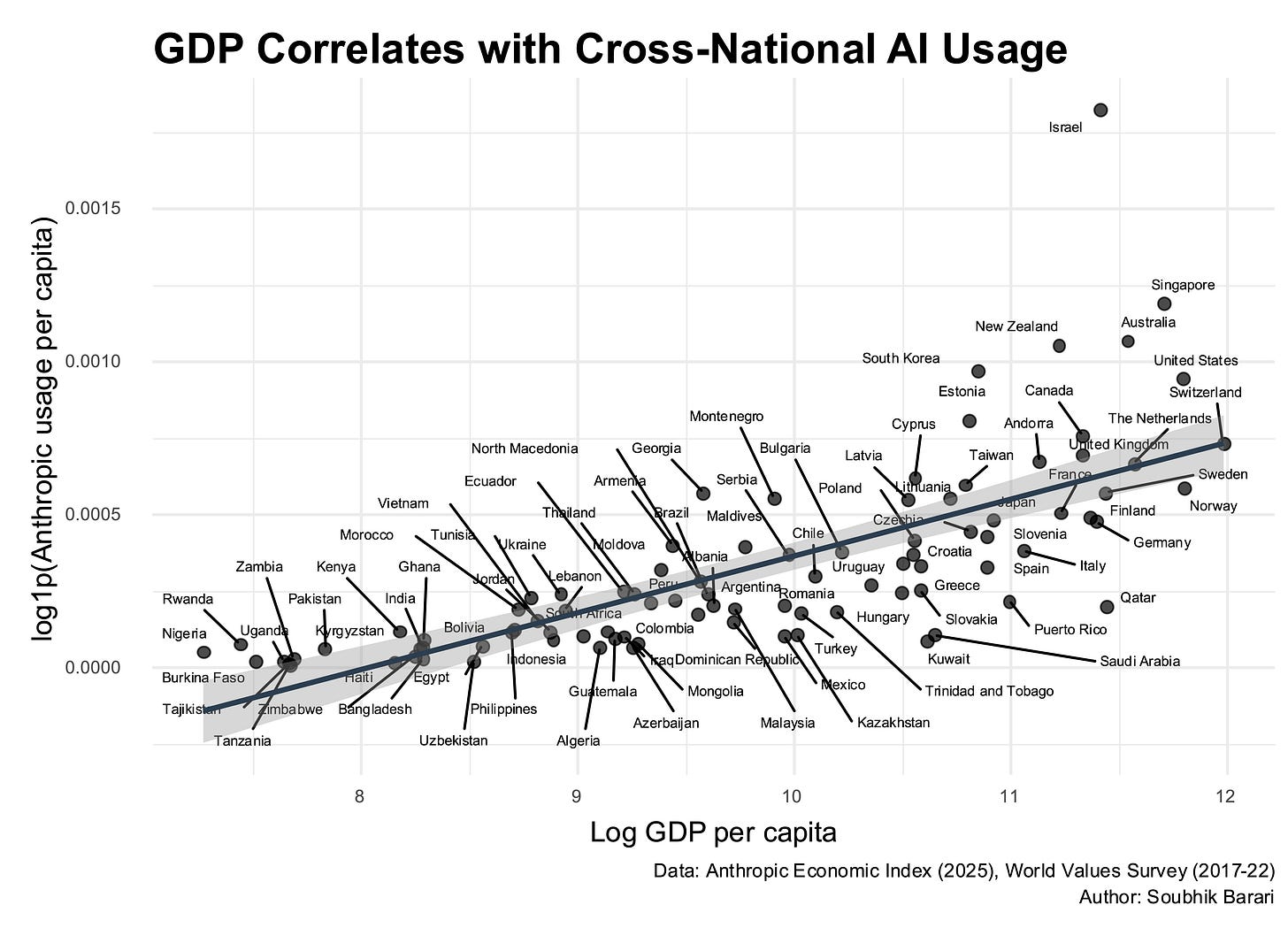

Anthropic’s Economic Index shows — using granular usage patterns of the company’s marquee AI platform Claude — despite large and rapid overall adoption, AI usage is concentrated in higher GDP countries.

This relationship is an extremely familiar feature of technological diffusion, seen with radio, telephone, the Internet, smartphones, and social media and now confirmed for AI.

As I have said before, it is useful to know that at the beginning of each new day the sky is still blue and the grass is still green. Knowledge is knowledge because it can be confirmed. But knowledge also needs expanding which requires us to traverse past well-trodden territory into the unknown.

Here we might ask: conditional on GDP and the things inside of its bundle (infrastructure, device access, digital literacy, a prevalence of productive knowledge-sector workers) what cultural dimensions track cross-national differences in AI usage?

The answer sits with one of the most impressive, sprawling, useful creations of modern survey research: the World Values Survey.

World Values and AI Uptake

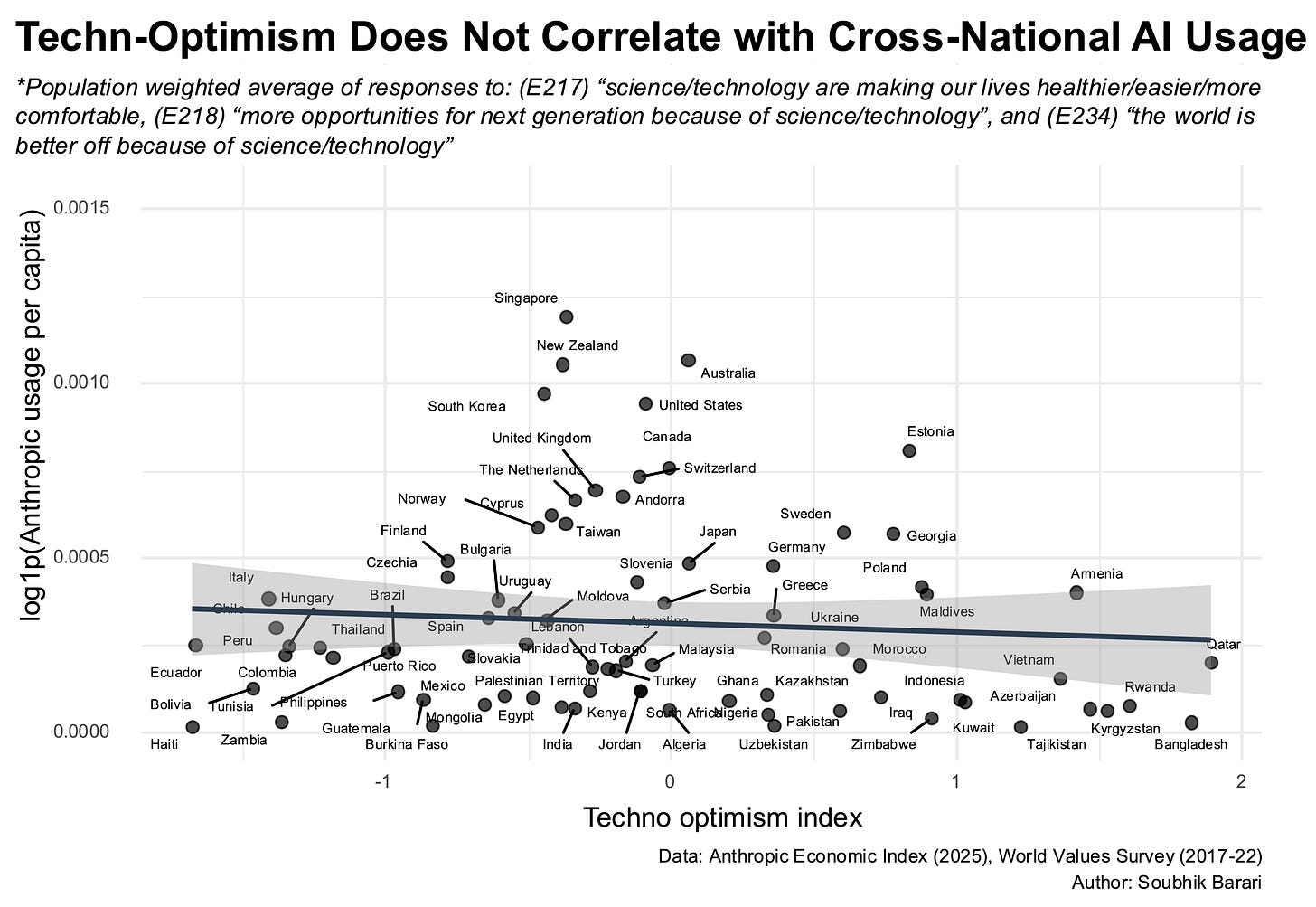

It seems strikingly obvious that Claude would receive more traffic from countries with more expressed technology optimism. The WVS asks several questions that reliably capture a portrait of ‘techno-optimism’: beliefs about whether scientific and technological progress improves life, create opportunity, and make the world a better place.

It turns out this index is a poor correlate with AI usage, both without and with adjustments for GDP.

The US is a leading Claude user, despite study after study finding moderately high rates of American techno-pessimism. We sit just below the middle of the world techno-optimism spectrum along with countries like Singapore, New Zealand, South Korea, and Australia. All of them, on aggregate, are AI power users.

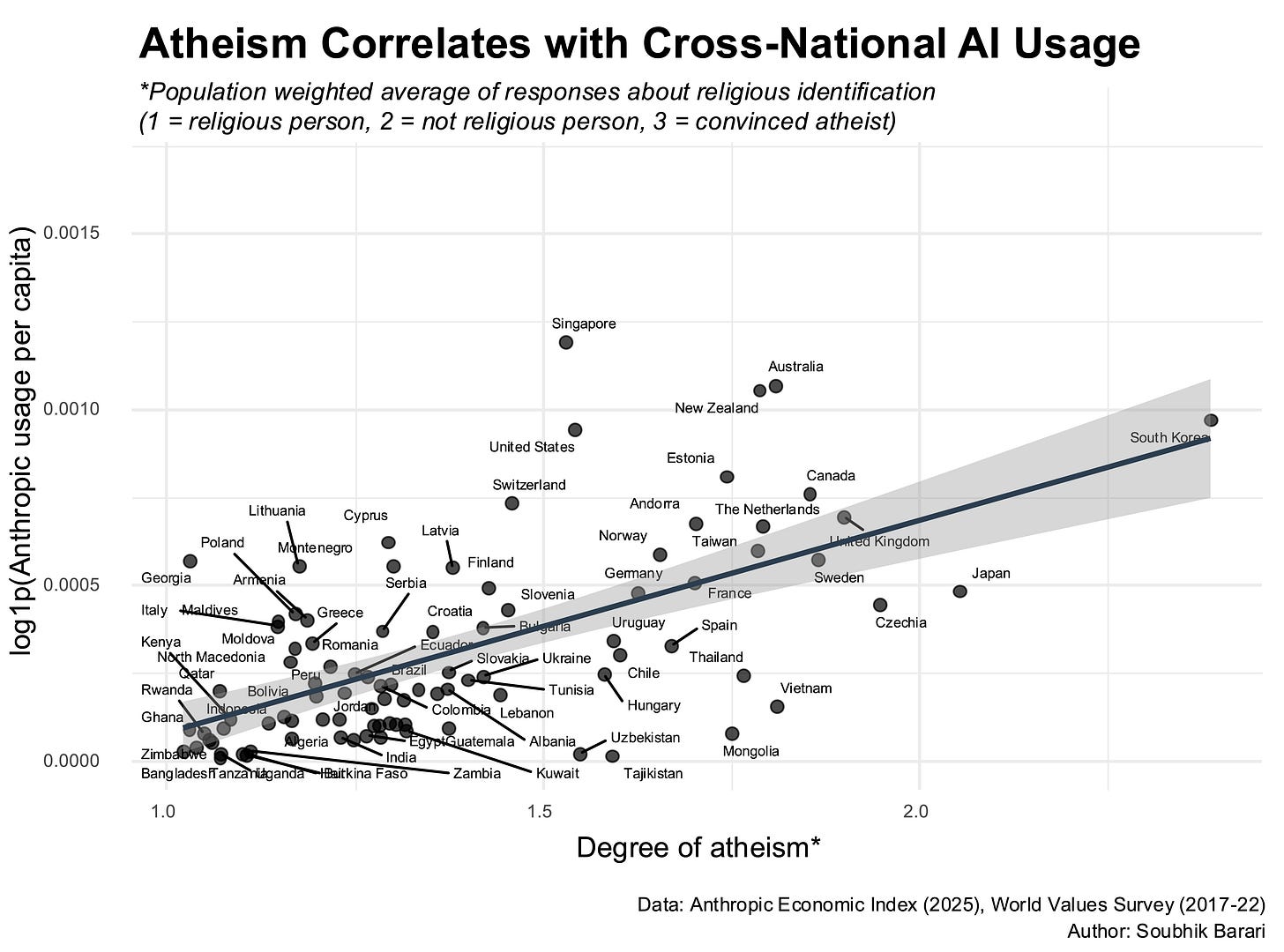

In contrast, surveys reveal a much stronger relationship between AI usage and religiosity. Countries with more self-avowed atheists are more often paying visits to Claude.

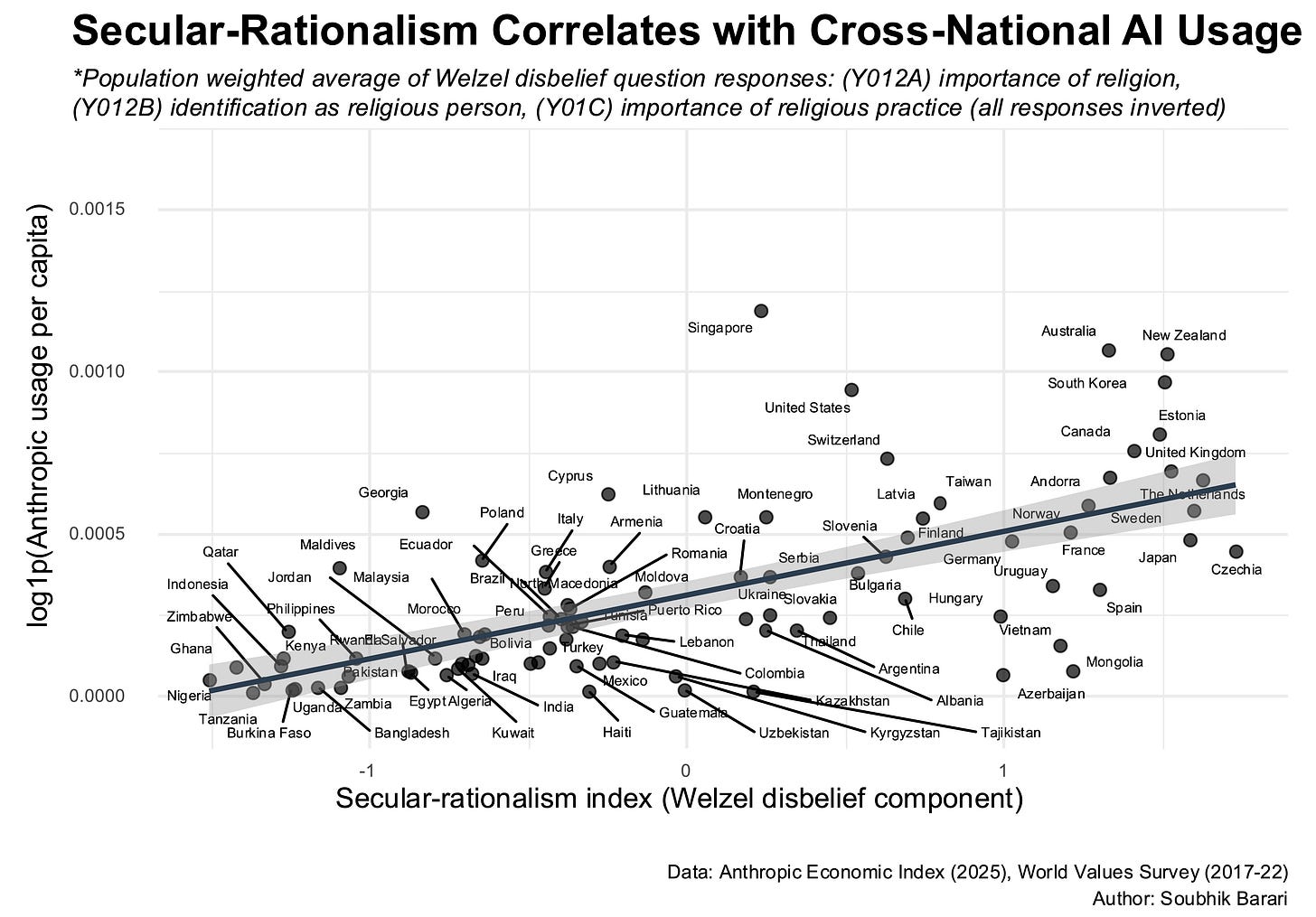

Beyond personal identification with atheism, Inglehart-Welzel theory of modernization (not without its controversies) emphasizes a broader dimension of secular-rationalism: movement away from traditional religious authority and toward rational, bureaucratic, and scientific authority. One component of that index—the “disbelief” items—captures declining religious belief and the reduced importance of religion in daily life.

If we take this measure at face value, we see an even stronger association between non-religiosity and AI usage. The raw correlation between this measure of secular-rationalism and this measure of AI usage is 0.65. For reference, the correlation between GDP and AI usage is 0.72.

Sure, once we control for GDP and we compare this to other attitudes, beliefs, or values, this could turn out to be a complete nothing burger, right? Except that’s just not the case.

Adjusting for log GDP, attitudes about religion — such as belief in god — turn out to be the only statistically significant predictors of AI usage.

AI vs. God

At first glance, this result is puzzling. If religiosity simply proxies skepticism toward new technologies, why wouldn’t explicit measures of technological optimism capture the same effect?

Expressed preferences (techno-optimism) do not always clean map onto revealed preferences (AI usage). AI may simply occupy a different category - it’s a gadget, but it’s also literally a friend, therapist, doctor, and LinkedIn post-writer. The grandchild of a dishwasher, it is not. It’s also possible that more AI usage actually dampens techno-optimism, but this data comes largely from surveys in the pre-AI era.

Still evidence does suggests that the more societies use AI, the more vocal its critics get. Perhaps with more techno-optimism comes more expectations and inevitably disappointment. Much like the dishwasher, the aggregate time-saving function of AI remains to be seen.

Another possibility is that religiosity captures something more specific than general skepticism. Religious institutions often provide sources of meaning, authority, and community that overlap with some of the roles AI is beginning to play: answering personal questions, offering guidance, or mediating uncertainty. In this view, religiosity does not just engender doubtful attitudes about AI, but avoidance. Data about Claude and ChatGPT usage show that richer (more secular) countries have the highest rates of personal (e.g., practical guidance), rather than technical (e.g., coding) conversations with AI chatbots. In more religious societies, such personal and social needs are being filled elsewhere.

A final wrinkle here is that AI discourse explicitly veers into the idea of “building god”. AI avoidance in more religious countries might naturally arise out of resistance against this (literal) evangelism. The pope himself — the premier opinion leader for a third of the world’s religious population — has weighed in, stating “it’s going to be very difficult to discover the presence of God in AI”.1

All that said, let us steer clear of any ecological fallacies: country-level data is a blunt instrument and these relationships do not show that atheistic individuals use AI more. We simply see a more ambient disregard for AI at a societal level in some places more than others. The claim here is narrower, purely descriptive, and subject to caveats and cautious interpretation, but the finding is striking.

As trust in institutions wanes globally, it’s hard not to notice peoples’ increasingly neurotic usage of chatbots — particularly among the young and the secular — as a deference to a kind of substitute authority.

If true, the real AI adoption divide is about God, not GDP.

Code and data here.

Pope Leo has notably since written extensively in nuanced, but largely cautionary ways about LLMs.