Who is Midwestern?

Go (mid)west, young data scientist.

Code and data here.

For my fellow New Yorkers and other coastalites, let me explain. There is a wonderful place that lies beyond these mean streets and concrete jungles: a land of lovely lakes, flat plains, and long drives, where ordinary people can pay in dollars and cents for fresh produce and single family homes. Where a little bit of cold doesn’t get anybody down (can’t complain, could be worse!). Where they ‘scoot’ and don’t shove, smile don’t scowl, where’s no sense running down the street and telling people about your feelings at the top of your voice, and where the letter ‘a’ in a word can sound anyway you want it to.

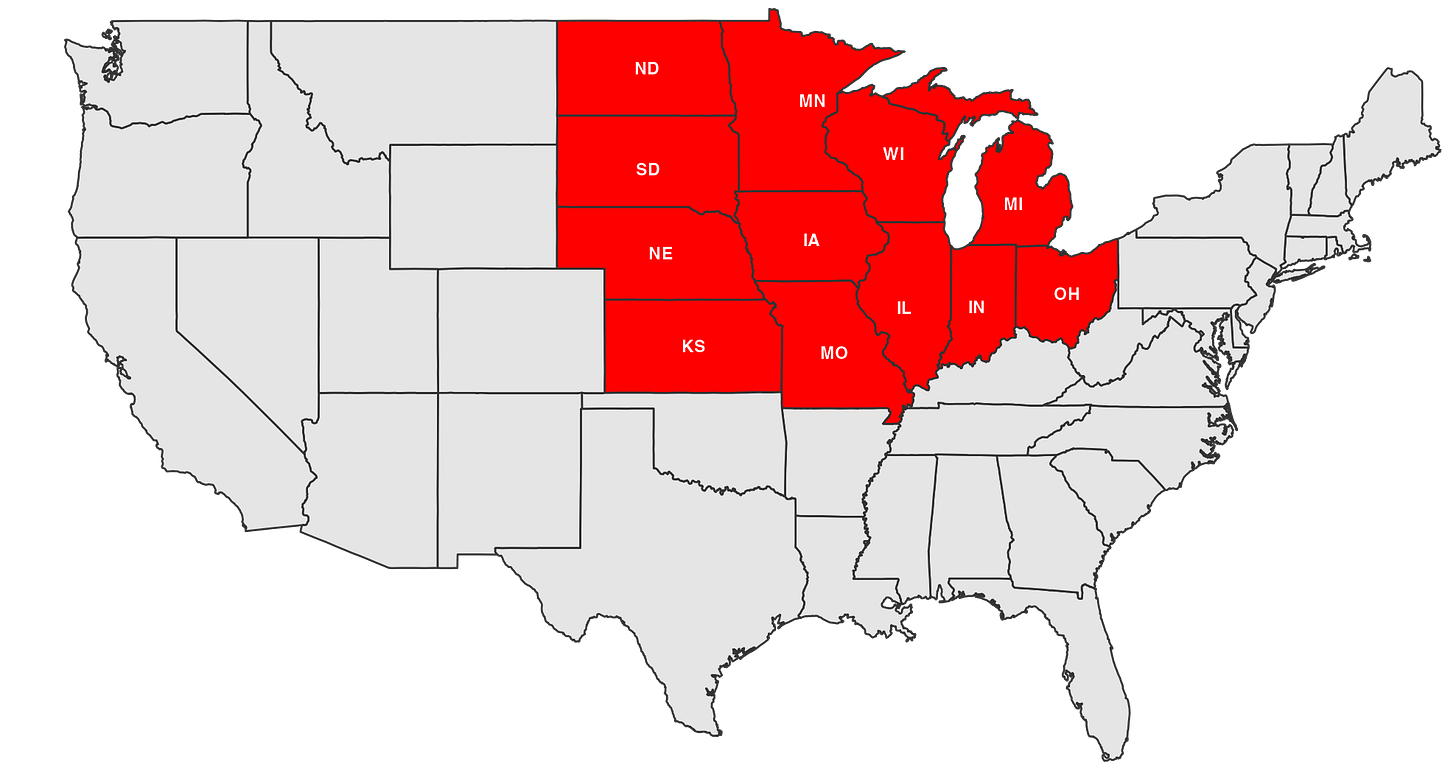

The name for this utopian wonderland — the Midwest — has been in common journalistic and popular use since the late 19th century. In his well-known travel writings, Tocqueville observed the region before the name even existed and described its people as marked by “that wealth and contentment which is the reward of labor.” 1950 is the year that it became the official Census region comprising of the 12 states as we know it today:

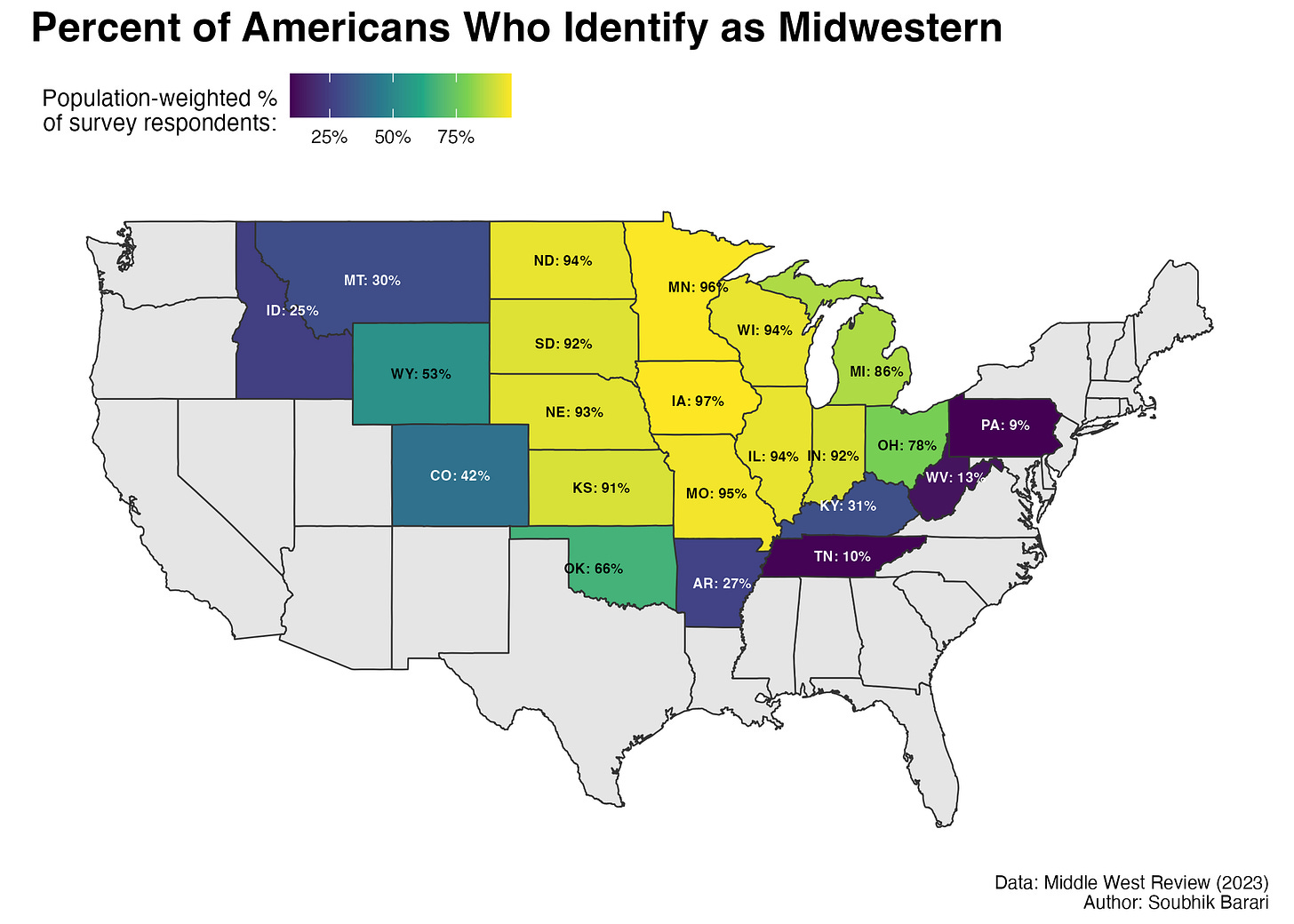

These map boundaries are settled and precise (for now), but who actually says they’re a Midwesterner? An impressive 2023 survey by Emerson College and the Middle West Review brings responses from 11,000 Americans to bear on exactly this question. Results are both unsurprising and surprising:

Though most of the ‘real’ Midwesterners indeed identify as Midwesterners, Iowa solidly emerges as the front-runner with about 97% of respondents from there embracing the label.

But why does Michigan (86%) lag behind Iowa? What’s up with those 22% of defectors in Ohio ? And what do we make of straggler like the some 10% of Tennesseans (solidly in the South) identifying as Midwestern?

Why do some states lean more Midwest? Perhaps it’s a story where agrarianism1 cultivates a greater sense of place-based identity in the Corn Belt (Iowa is the largest per-area agricultural producer in the country) and “Midwest” simply and logically describes that place. Economic belonging may also precede cultural belonging. People whose work has historically flourished in a region — in the Midwest, not just farming but unionized trades — may develop more positive associations with that place than with America at large where those industries have, on average, stagnated.

Perhaps, in some cities or metro areas, a greater affinity or prevalence of the mother tongues of Midland English, the cornucopia of similar accents running from western Pennsylvania through northern Oklahoma, all recognizably different from any on either coast. (A fun fact here is that Middle American accents formed at warp speed by linguistic standards, many of its defining features emerging within a mere century. Compared this to the nearly thousand years it took for dialects in the British Isles to form).

Perhaps some states are more distinctly “Midwestern looking” or were stronger migration destinations in the 19th century, both direct consequences of the Homestead Act of 1862. And although regional mobility is infamously low in the U.S., people still do move around and it’s reasonable to think many of those outer-state stragglers are just core-state transplants. Idaho in the 2020’s is what Colorado was in the 2010’s.

So then why do some states lean less Midwest? States like Ohio and West Virginia sit at the crossroads of many competing regional labels — Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic, Midwestern — and there’s only so much geographic identity you can hold in your head.

As our Ohioan vice president reminds us, Civil War memory is also still very much alive, and Ohio sits squarely at its center. The Midwest may ironically have the strongest claim to that history as the 12 states ultimately supplied more infantrymen who died in battle than either the industrial Northeast or the Deep South. But if your ancestors fought and died in a war long framed as a showdown between North and South, you may have grown up heralding one of those identities instead.

Clearly the explanation is cultural, in the broad sense an accumulation of language, economy, history, and habit (things that this data can’t speak to, but gets the debate started).

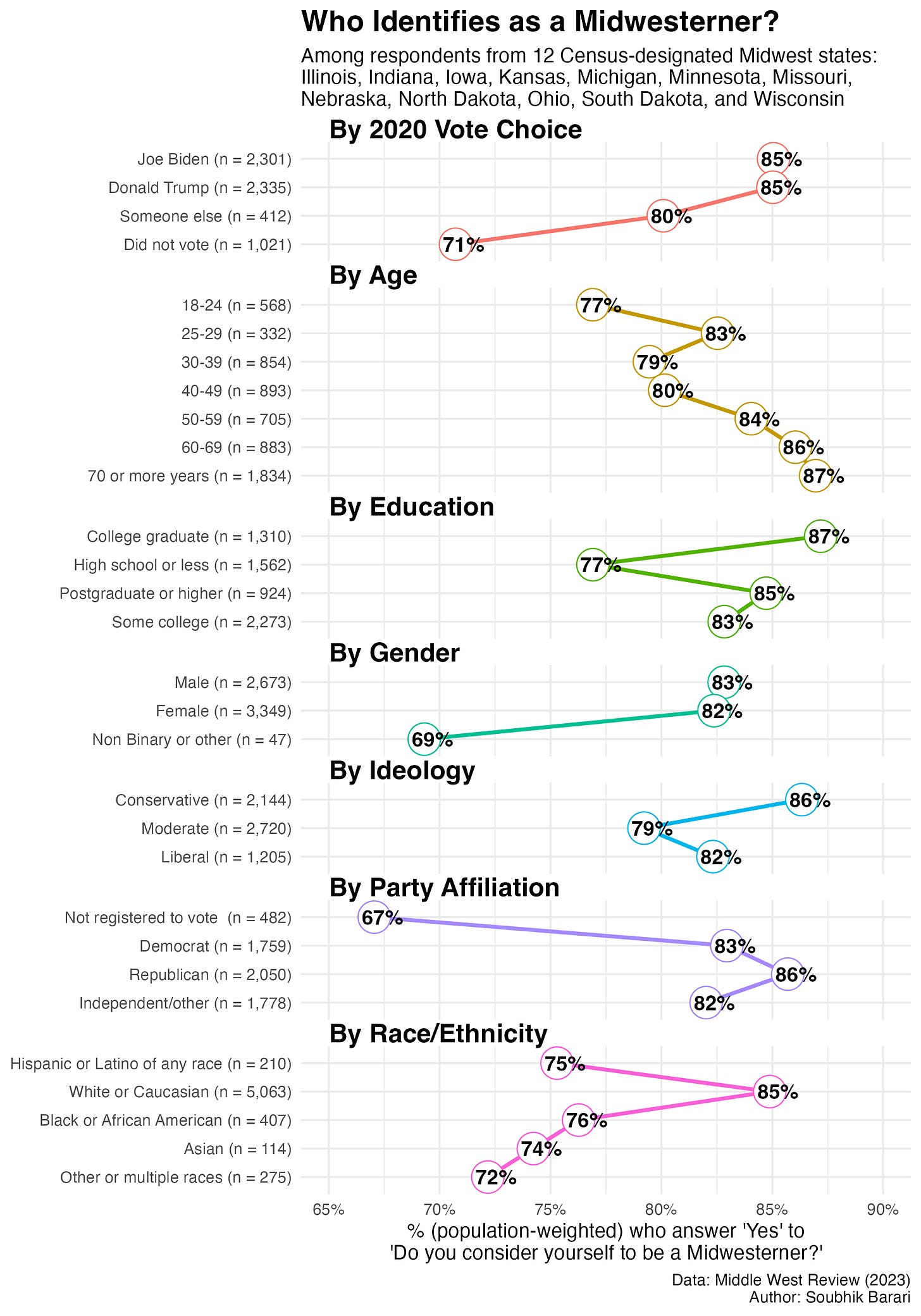

This survey data can help us uncover who has more of this regional identity and the answer is: older folks, White people, conservatives, and degree holders.

There’s the obvious moral particularism vs. universalism explanation for this. Conservatives hold more particularist, clannish attachments (it’s ‘get out of my country’) than liberals who hold more universalist and cosmopolitan beliefs about the world (it’s all stolen land!). Liberals are also more pessimistic about America as a whole and are less likely to express national pride and this could naturally extend to regional attachment. Though we should be clear 82% of liberals owning their Midwestern-ness2 is still a very high number!

What’s interesting is that both conservatives and degree-holders are more likely to identify as Midwestern and those are increasingly diverging groups. Both types of people harbor a stronger sense of participatory spirit, but to different kinds of institutions: conservatives are more likely to go to church and the Midwest is generally more church-going than the coasts, degree-holders are twice as likely to vote and volunteer as non-college goers. All else equal, these separate routes may still lead to the same feeling of place-based belonging.

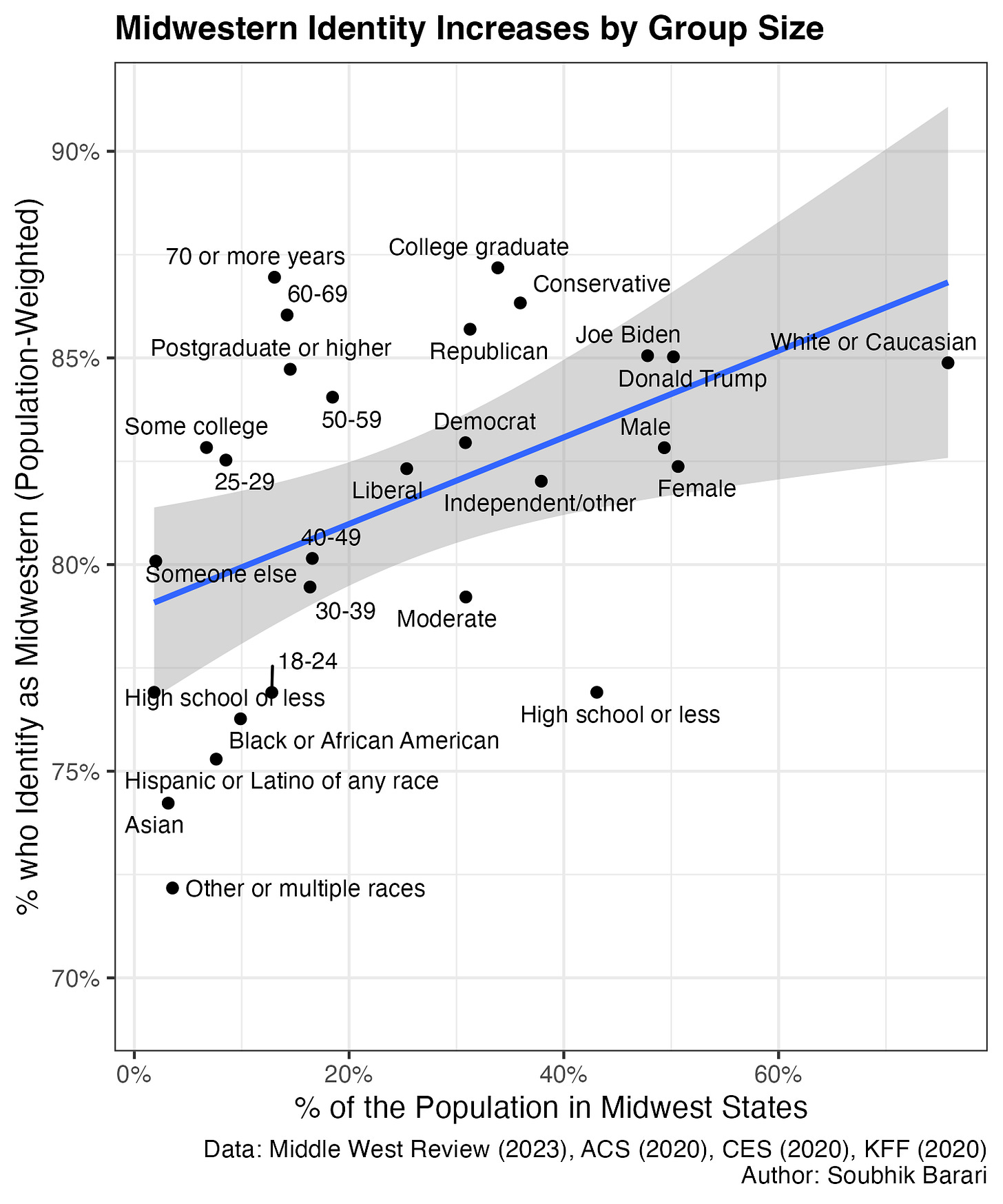

Finally, if you throw in the size of these groups in the actual population, there’s also a very clear pattern: bigger groups clearly have a stronger sense of regional identity.

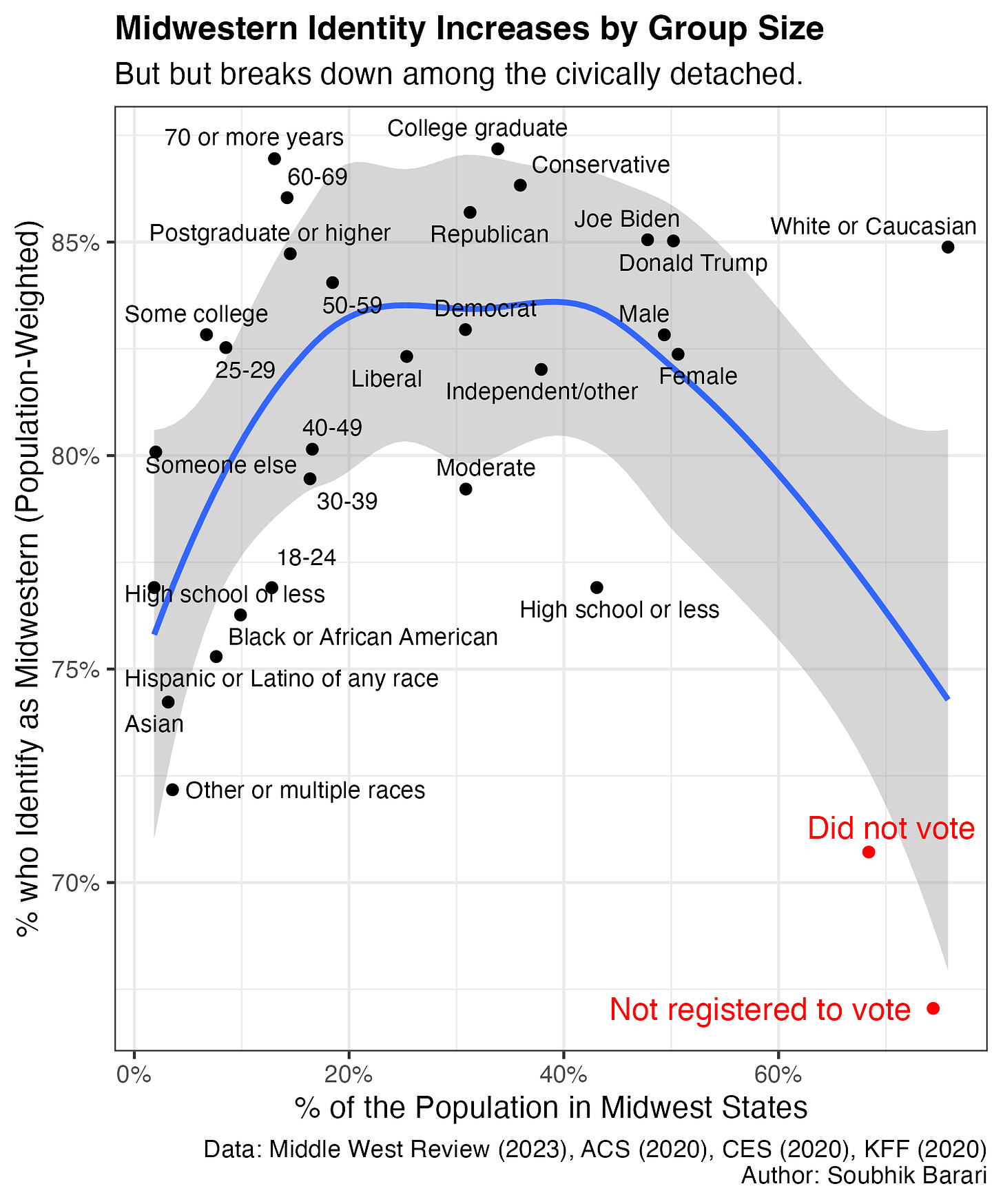

But notice that I left out a couple of groups, specifically those who neither vote nor are registered or to vote. Check out what happens when you re-include those and draw a line of best fit:

So clearly there’s an important third variable related to civic attachment or participation missing in the data. Groups who are part of Groups™ are more likely to identify with other Groups™ but groups defined by lack of group-ish-ness, less so. The chart, read alongside the diploma divide, shows the “high school or less” group moving away from capital-G Group status.

Regional identities matter (or do they?)

“Like all regular people I grew up with in the heartland, JD studied at Yale, had his career funded by Silicon Valley billionaires and then wrote a best seller trashing that community. Come on, that's not what middle America is.” — Tim Walz, 2024

Nationalization is perhaps the dominant theory about American politics in the 21st century. Importantly, Dan Hopkins, one of its leading hypemen, has clarified (in the book itself if you read carefully) that does not preclude strong regional or state identities in this day and age. It’s just that they don’t matter for organizing most peoples’ politics in an era of strong national party brands.

At first, it would appear that political elites do not believe this. From Tim Walz’s fandom of Menards being a central theme in his candidacy to much of the campaign and media class’s obsession with ‘heartland appeal’ to the sneery pejorative of ‘flyover country’ and its equally nose-thumbing re-appropriation3, middle America is firmly lodged in our collective political imagination.

These appeals to regional identity make more sense when you realize three things.

First, as the dueling 2024 Vice Presidential candidates clearly demonstrated, “Midwestern values” pretty much mean whatever you want them to mean: middle class, unions, church, college football, niceness, toughness, and everything else. To be sure, there are limits on how far you can take framing effects for core political issues. But beyond those there is an extremely broad set of political concepts, terms, and symbols that are just empty rhetorical shells ready to be filled by media narratives and elite cues.4 Just because conservatives adopt the midwestern mantle more often than liberals, does not mean the Midwest is fundamentally conservative.

Second, regional identity, and identity in general, is in equal part doing as it is being. It’s hard to feel like a Midwestern, a New Englander, an Asian American, a pickle ball champion, or anything at all, just sitting all alone in your basement. Identities are created, not assigned, and they are created with others. Participation also predicts participation5, so appeals to Heartland values electorally may function more to mobilize turnout, than to change hearts and minds. Being more embedded in a place may also literally make easier for you to register to vote.

Third, regional identity matters because regional economies differ, and voters strongly respond to those differences up and down the ballot. People in commuting zones hit harder by the “China trade shock” literally started watching Fox News more than in other areas. Campaigns respond to this and know to play up the ‘bring the jobs’ ads over the ‘protect the safety net’ ads in districts with higher unemployment. And given the common story of manufacturing decline across the Rust Belt, it’s hard not to make a stump speech in Flint, Saginaw, or Detroit (all cities a whopping 30% smaller today than twenty years ago) without reaching for the phrase “industrial Midwest.”

The Midwest here is just a ‘case’ for the social science of regional identity, but a very important one.

Epilogue: On the topic of regional musical appeals, Toledo, I’m sorry you guys get such a bad rap. For every John Denver, find yourself a Chappell Roan.

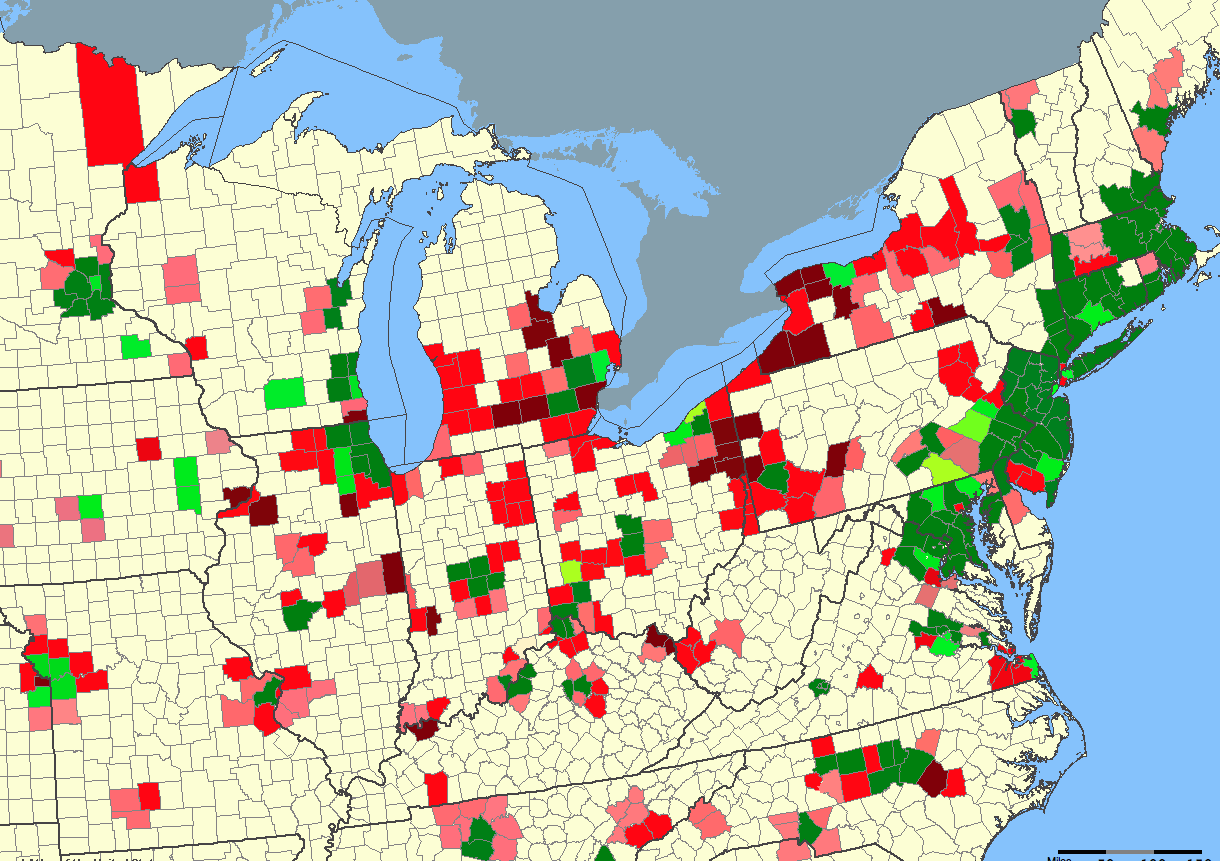

Rapidly switching between my map and this map, you can basically conjure up the correlation in your mind’s eye.

Alt: Midwesternism, Midwesternity, Midwesternality, or, if you prefer, the highly elevated “Midwesternationalism”.

When I used to help run Harvard’s online survey panel, one of our participants would snidely sign off every email “Sincerely, from flyover country.” It is aptly described as “a stereotype of other people’s stereotypes”.

Zaller vs. Converse debate aside, political scientists have been saying some version of this for more than a hundred years.

There is some interesting counter-evidence to this.

Is this a comment on my cooking?-Midwestern mother in law.

It would be interesting to see this broken down by county. Far western New York State feels more Midwestern than Northern Atlantic to me. Here in my home state of Colorado the northeastern Great Plains have a very Midwestern culture as opposed to the San Luis Valley or the Western Slope.