Political competition doesn't really work

Three facts about how political competition in the United States mostly fails (written from the tears of a hundred economists).

This is the fourth post in a series of posts about a phenomenon in American politics called (by me) the "polarization paradox". You can read about what exactly that is, some examples of it in recent politics, and its six root causes here.

For the data nerds out there, you can now download all the code and data behind this and every past and future Somewhat Unlikely post.

There’s long been a refrain that American politics, like anything American, needs more competition. One line of reasoning goes that "firms" in the politics "industry" (politicians) need a healthy injection of competition on the political "marketplace" (elections) in order for "consumers" (residents, donors, voters) to have access to better "products" (laws as they are

'designed' and 'manufactured' on the legislative floor).

This is a bit of a strained metaphor since private goods produced by firms for paying customers are fundamentally different from the public goods all Americans - whether or not they ‘pay’ with their votes - should expect from government. Nevertheless, many Americans do participate elections with the same mindset that they check out on their Amazon Prime shopping cart. The demand for competition might be there after all. But does competition actually help?

To lay down some clear definitions, there’s three different types of political competition worth considering (if you're already a politics junkie, you know this already so skip ahead to the 'takes').

There’s electoral competition, which concerns candidates in an individual election - a competitive race typically being one where the top contender candidate appears to have more a single digit polling advantage than their opponents, a toss-up being one where there’s no clear front-runner at all. Conventional wisdom says this forces candidates to have a meritorious battle of ideas and cater to the ideological center.

There’s party competition (you could also call this coalitional or factional or legislative or governing competition) measured by the margins between factions in control of the government itself (in whatever branch at whatever level). Conventional wisdom, similarly, says that elections that produce razor-thin legislative majorities are a “mandate” for cooperative bi-partisan policy-making — you could basically create a soundboard of party leaders saying this over the years.

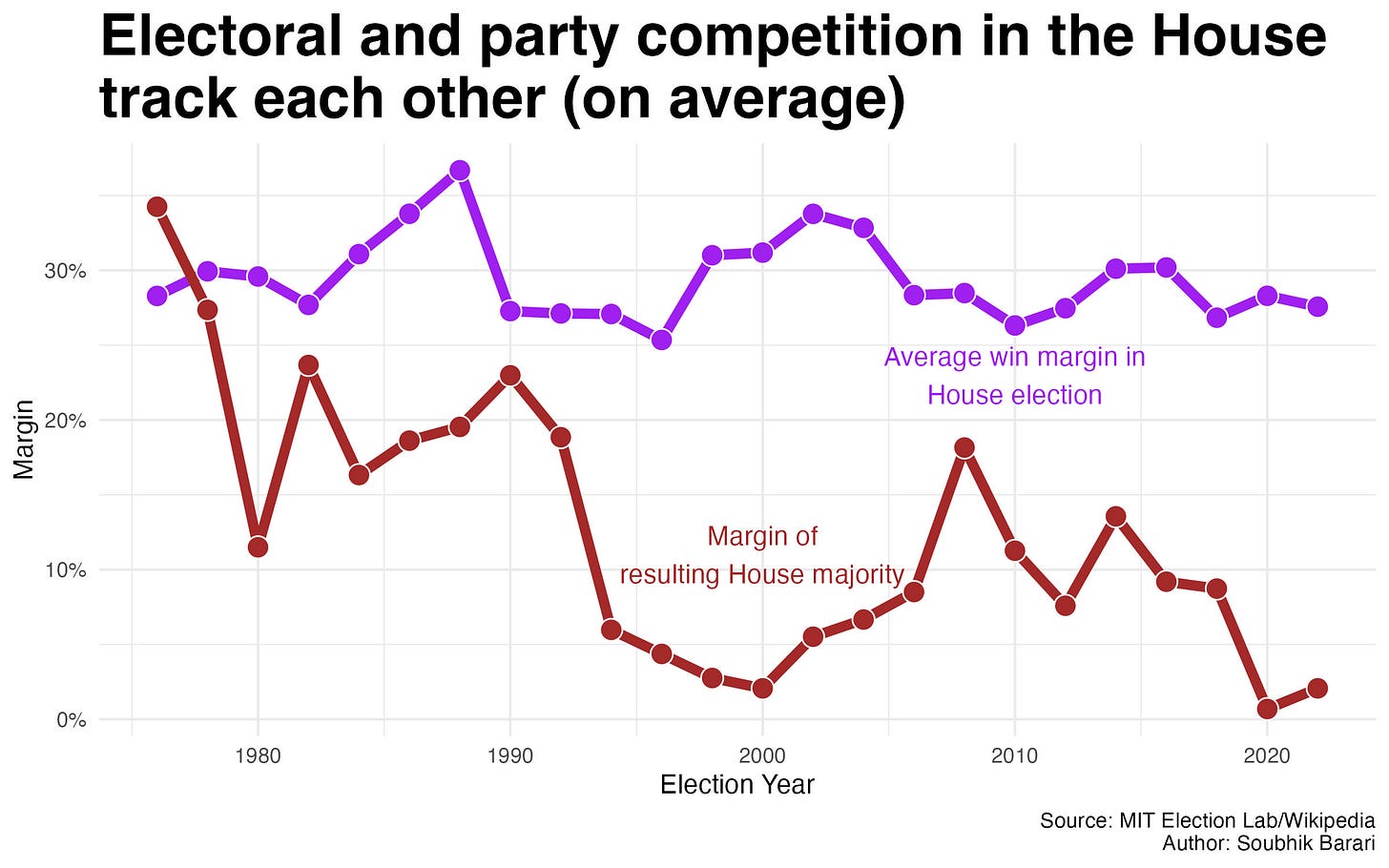

These two types of competition are conceptually different, but are empirically related. If you squint, you can see that the margins of House majorities over the last 50 years generally track with the average competitiveness of the elections that produce those majorities.

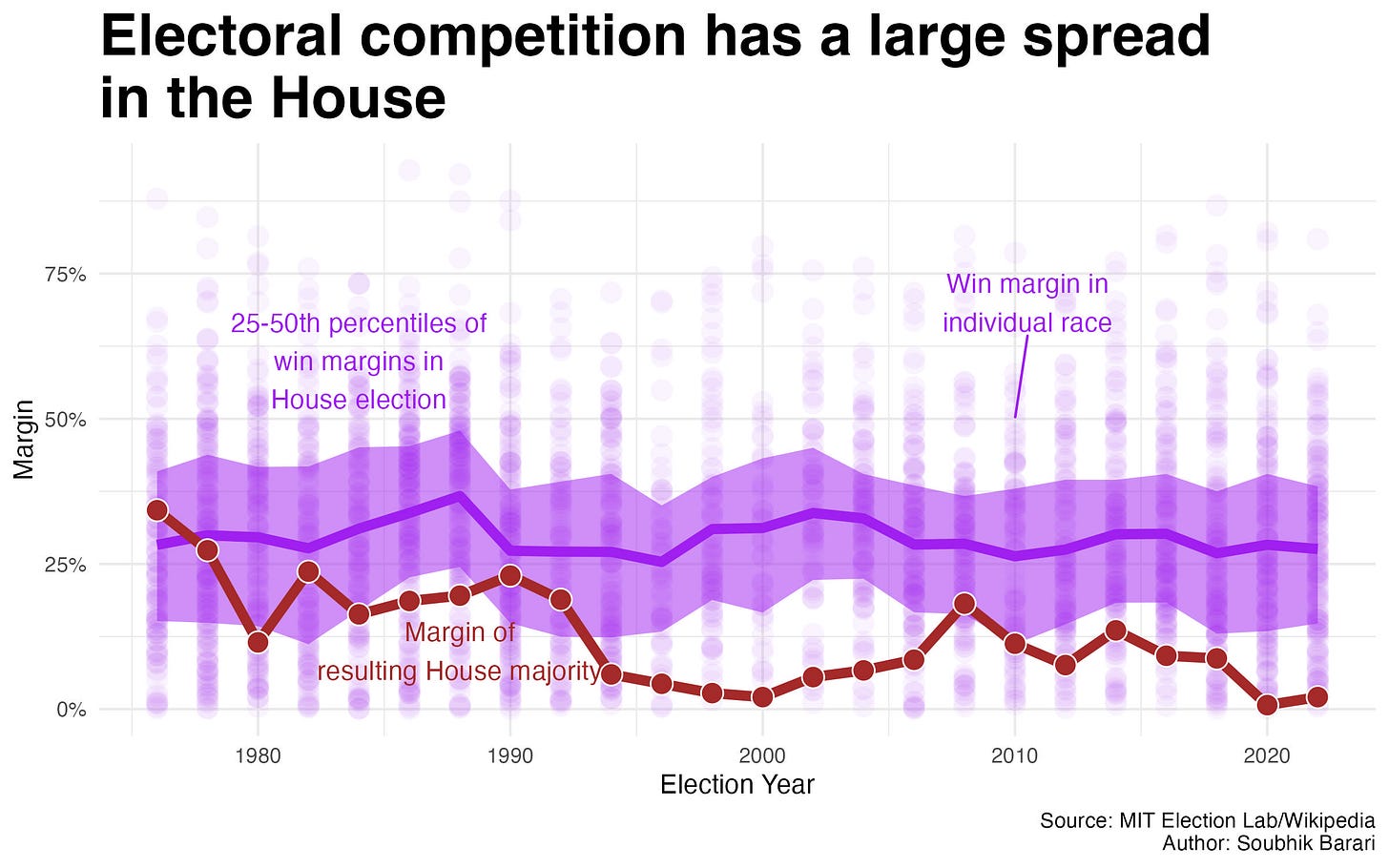

It’s just a wee bit misleading because if we blow up these averages to look at the percent margins across all races, it’s clear that our slim majorities aren’t because of universally greater electoral competition:

This drift is a good reason for treating these two concepts as distinct. It’s also a great illustration of the polarization paradox I’ve been harping on about: stable politics in the broad view (the electoral map) but hair-pin uncertainty in the political outcome that matters (actual legislative seats).

There’s a third kind of political competition, but it’s a little less concrete, less obviously quantifiable, and doesn’t have to do with the behavior of elites which is what I mainly want to talk about. There’s one big feature (or bug) of our politics that complicates any serious discussion of this third one so I’ll leave you in suspense about what that is until the end.

Okay, now here’s three important things you should know about political competition.

Fact 1: No, political competition doesn’t bring moderation and cooperation to policy-making.

This conventional wisdom is wrong both in the context of electoral and party competition.

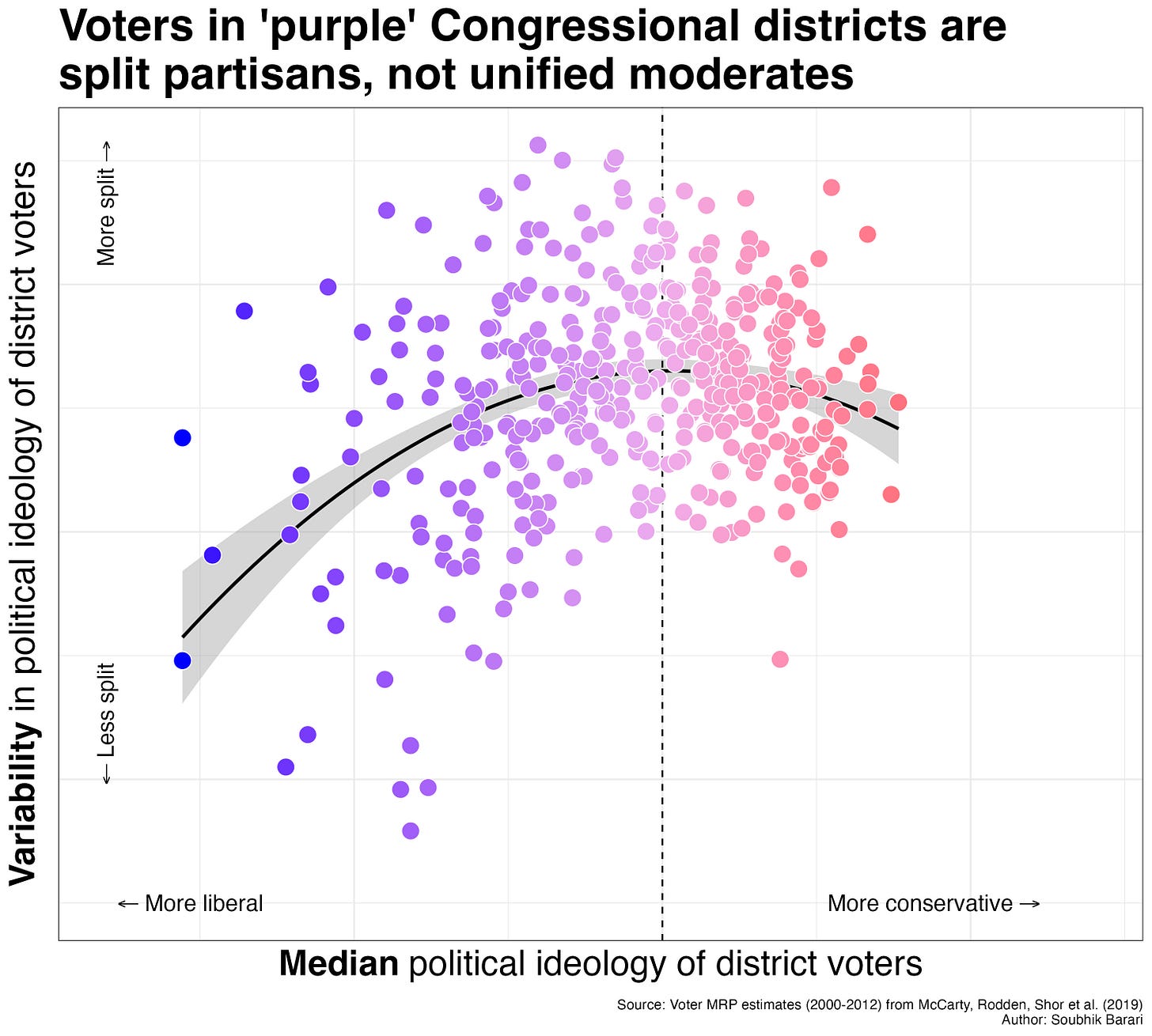

The claim that competitive elections help to elect moderate and cooperative politicians is wrong for an intuitive, but somewhat surprising reason. When I say the phrase ‘purple America’, what do you imagine? Chances are you’re probably thinking of a particular kind of voter — likely older, likely white — who lives in a particular kind of place — the suburbs — and holds centrist political views.

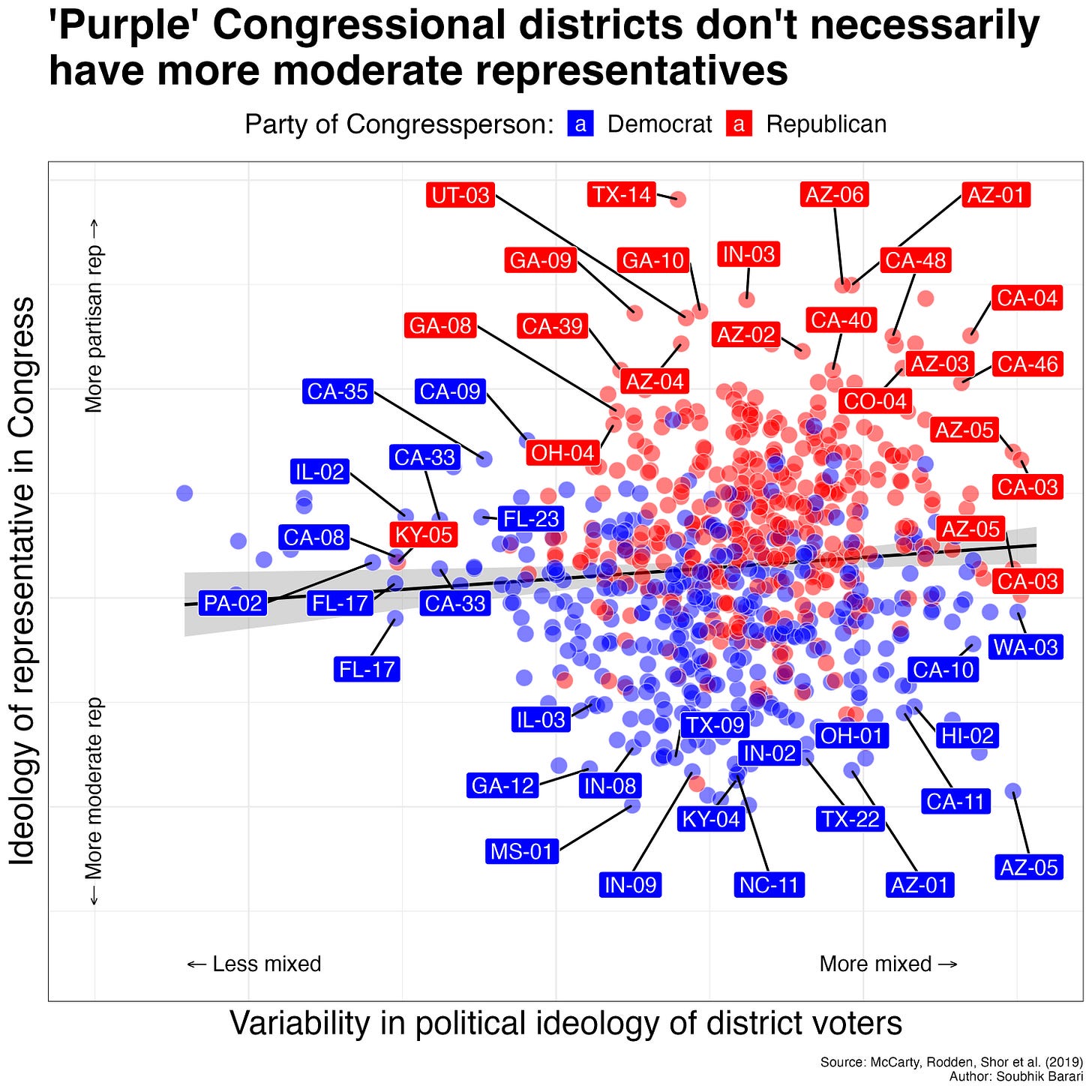

Well, those purple parts of the election night map are indeed likely to be the outlying suburbs of large metro areas. But purple America, as you can see in this graph of U.S. Congressional districts below replicated from a recent paper, is still mostly composed of deep red and deep blue voters, not these imagined purple people!

So in effect, if a candidate is running for office in one of these so-called ‘purple’ districts — unless it is a non-partisan office that is extremely de-politicized — they don’t have much of a moderate core to cater to. Rather they will tailor their campaign to their party’s voter and donor base, which is either very blue or very red.

Once elected, representatives of these so-called purple district vote for policies that tend to lean in one direction. Mapping the expressed ideology of House representatives’ roll-call votes over the last two decades reveals exactly this:

In other words, a candidate’s party at the end of the day is a much better predictor of their policy platform (and actual policy-making behavior if they win) than whether their district has a mix of moderates, liberals, and conservatives to compete over for votes.

Fast forward to after election day, after these close races are won, and after the calls for “bipartisan policy-making” are made, how does the resulting legislative body actually govern? In her book “Insecure Majorities”, political scientist Frances Lee shows that state legislatures with thinner legislative majorities, tend to pass more polarizing policy outputs in one ideological direction, implying less, not more cooperation.

So party competition, like electoral competition, backfires. When a party — either in the minority or majority, be it Congress or the state house — anticipates that power may change hands in the next election, its members have strong incentives to rally behind the party brand and differentiate themselves from their future opponents as much as possible. They do this instead of converging to the ideological center (as is often mistakenly believed) in the hopes of picking off voters leaning towards the other party.

Fact 2: But, zero party competition has historically been very bad.

It is tempting to then say that political competition is not useful at all. In fact, political competition has helped uniformly transform the United States into a livable, developed, advanced industrialized nation.

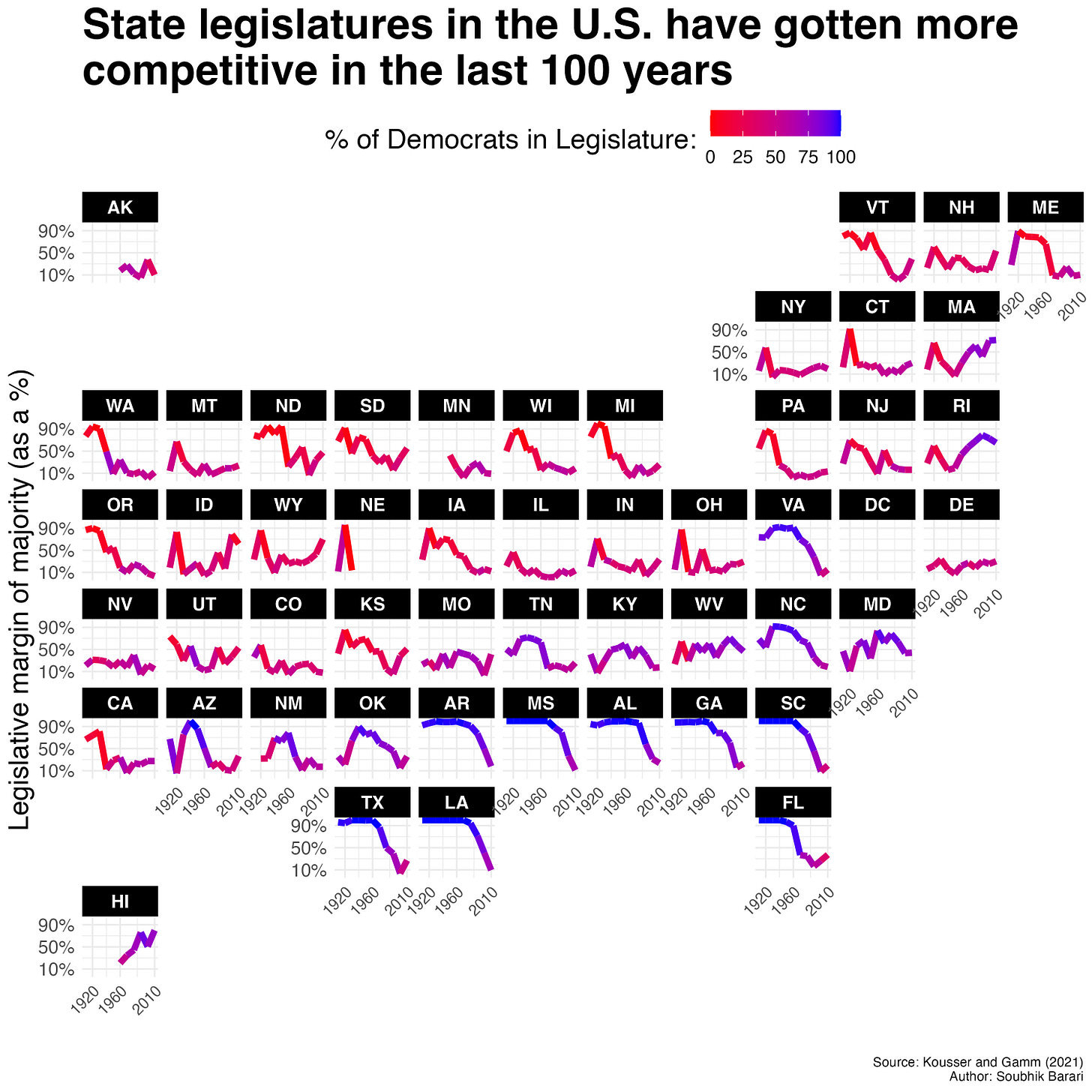

To see this, we turn our gaze from Capitol hill to the state house, where legislatures have universally become more competitive between Democrats and Republicans over the past century — most starkly so in the South:

Again, this tracks with the average state house election becoming more competitive across the country. As political scientists Gerald Gamm and Thad Kousser show in a sweeping 2021 evaluation of state legislatures, this has resulted in a ‘lifting of all boats,’ so to speak, on the basic elements of human well-being and prosperity: literacy, earnings, infrastructure, safety, infant survival, and life expectancy.

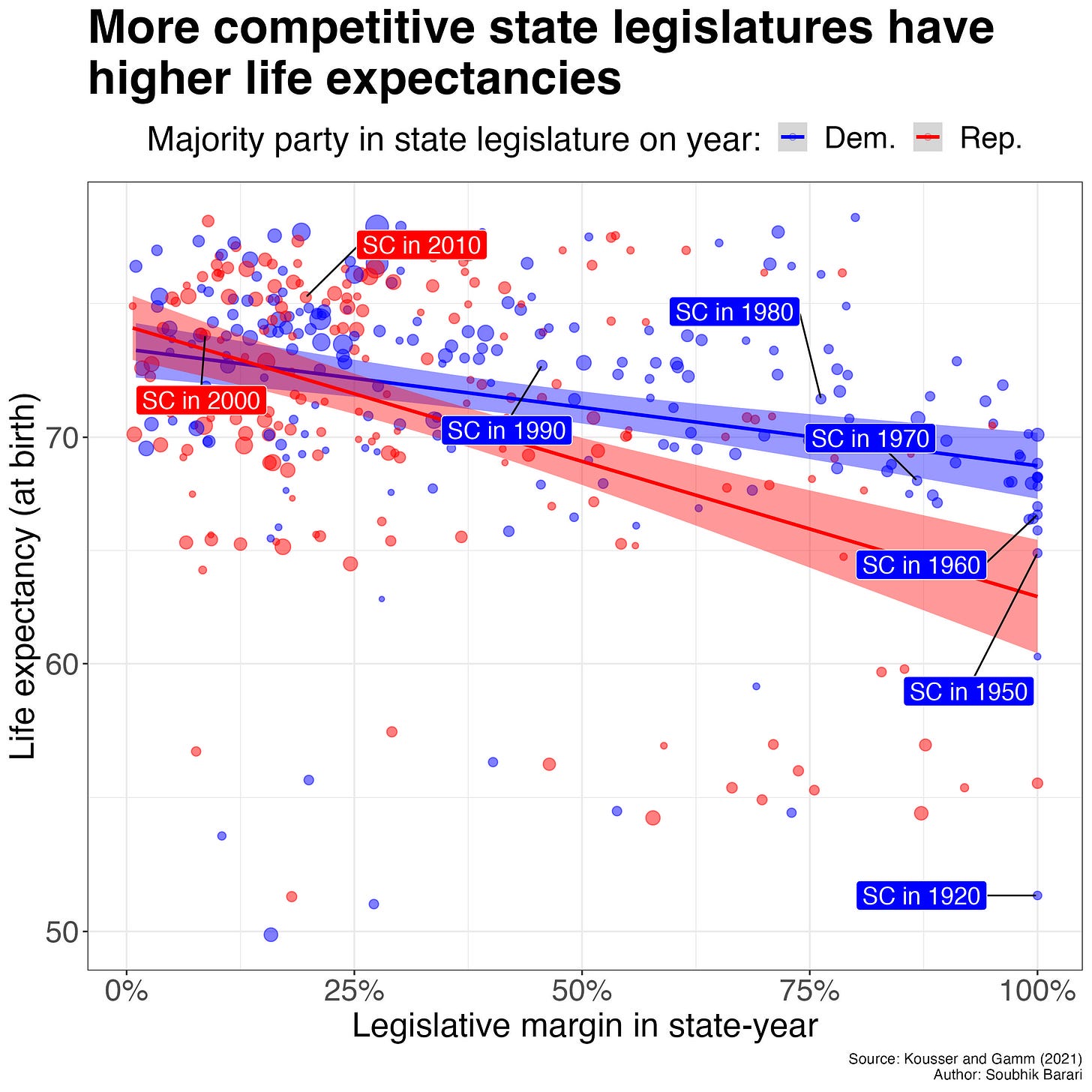

To take an example, a person living in South Carolina in 1920 would likely not have lived much older than 50 years. Fifty years later in 1970, after the authoritarian one-party grip of Democrats in the South began to loosen, the life expectancy in South Carolina shot up by 30 years (this is true even after adjusting for a myriad of other state-level variables). You can see this correlation playing out over time and geography here:

As with today’s Congress, Republicans competing for control of the state house, had an incentive to show how they differed from Democrats and vice versa. Except historically, the way that the two parties could do that was by creating relatively novel mass social programs that could appeal to broad swathes of the state-wide (white) electorate.

So yes: zero party competition has historically been very bad, creating enclaves of essentially third-world, authoritarian rule clustered in the U.S. South. Party competition created the incentives to shape the modern American state. However, now that the modern American state is largely developed, the conflict line between the two parties has shifted past these material issues. Competition today is unlikely to bring about policies or programs that produce similar leaps in living standards for all Americans like it once did.

Fact 3: Neither electoral competition nor party competition really increase productivity.

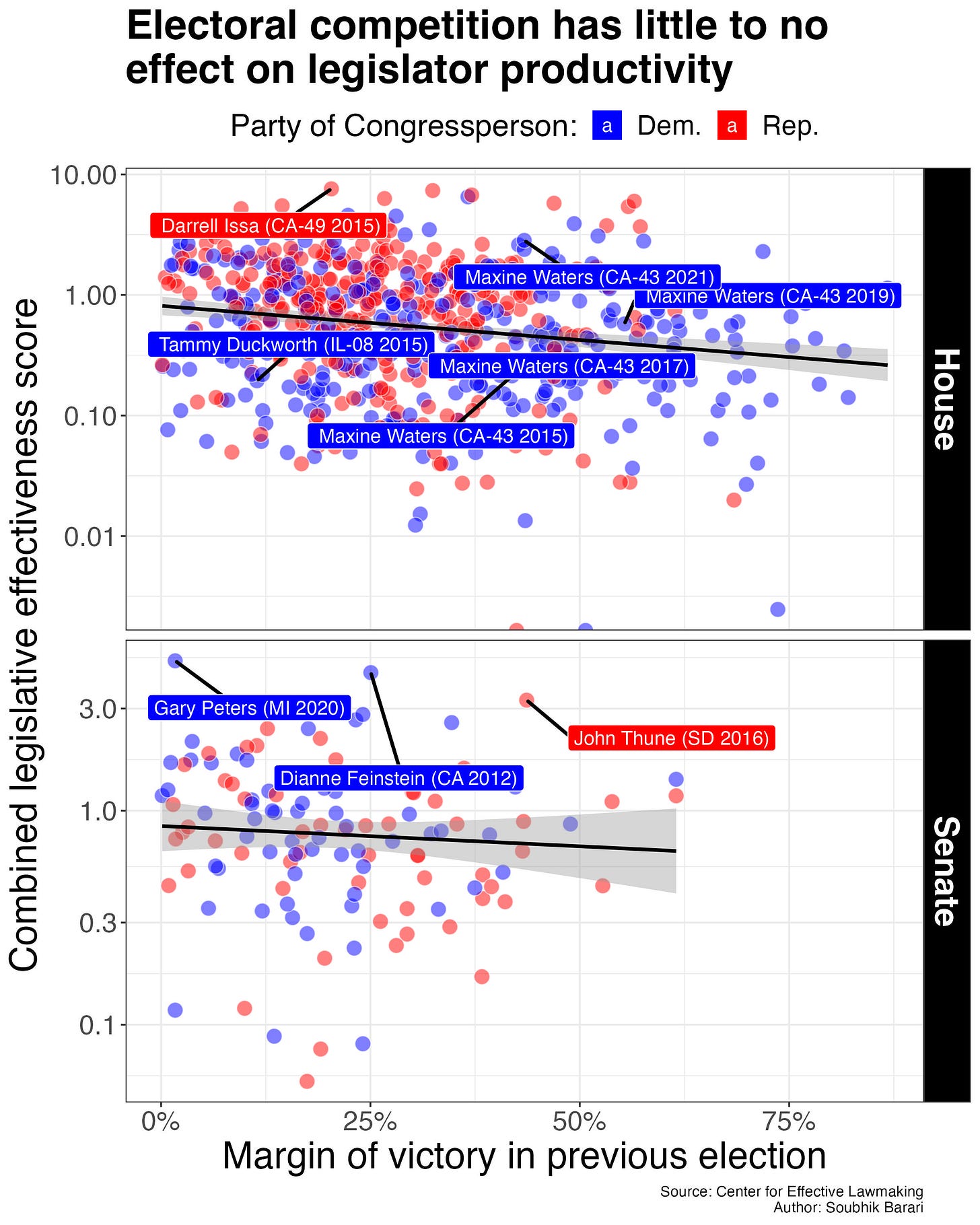

One of the fundamental claims of the politics-as-an-industry analogy is that political competition, like economic competition, increases productivity. This is also wrong … or at least overblown.

We can confirm this by replicating the results from a 2018 paper from Michael Barber and Soren Schmidt that tests this claim. Like them, I found a modest to statistically insignificant correlation between a member of Congress’s margin of victory (lower = more competitive) and legislative productivity as measured by an effectiveness score that combines different kinds of productivity (substantive bills making it past committee, bills turning into law) adjusted for the baseline productivity on the floor each session. Here are those correlations for each chamber in the years 2010-2020:

Note that the vertical axes are on a logarithmic scale and they do not account for anything about the districts — when they’re on the usual linear scale the relationship looks even more underwhelming, and when we adjust for the session of Congress, the elected candidate’s party, the elected candidate’s seniority (if they are an incumbent), and the district itself the relationship reverses direction entirely.

Contrary to belief, legislators hailing from less competitive districts are about as productive as their colleagues who’ve barely made it into Congress. Vulnerable politicians are simply choosing to channel their time and resources toward other things that are not law-making (bad) — things like campaigning (meh), fundraising (meh), but also constituent service (good!).

In theory, party competition could also make legislators more productive. It could, for example, force a slimly elected majority to juice their coalitional advantage to pass as much useful stuff as they can. The Democrat’s first Congressional session after the 2020 midterms was a great example of this, but unfortunately it may be the exceptional circumstance (unified government 😱!) that proves the rule. Thanks to the institutions that govern (read: obstruct) law-making like the filibuster, the basic fact that we have a bicameral legislature where divided government can completely fragment the otherwise leading party’s power (thanks, Obama), and the minority party’s rally-behind-the-party incentives (see Fact 1) — competing parties in government are not necessarily something to aspire to.

There is one, and maybe only one, productivity-enhancing effect of electoral competition but it doesn’t have to do with politicians. Competitive districts makes for more productive citizens: they are more politically engaged, more political knowledgeable, and possibly more likely to turn out to vote (though some natural experiments with close elections suggest otherwise).

What about the competition of ideas?

In short, one of the main reasons that both competitive elections and competitive parties backfire — in the contemporary context of American politics, to be clear — is that party loyalty ultimately crowds out any room for moderate policy platforms, bipartisan deal-making, or policy-making itself. Which brings us to the third type of competition that goes deeper than just the arrangement of voters in elections or law-makers in the legislature: the ideas competition.

This sounds like something your local art fair puts on every year for kids. That ideas competition sounds delightful. The one I’m talking about is about increasing the supply of political ideas for voters and politicians to get behind beyond the binary of solutions offered by the current two-party duopoly. Practical suggestions to do this include rallying support for third parties, holding larger and more open primaries, and implementing systems like ranked-choice voting at all level to allow voters to simply ‘pick more ideas’.

These are not just academic suggestions anymore, but proposals that are gaining serious traction (and funding) in recent years. I’ve reached my bubble-busting quota in this post, but there are just as many serious issues with these proposed reforms as there with shifting districts and legislatures. On the demand side alone, crowded primaries are chaotic, ranked-choice voting is confusing, and despite what people say in polls, third parties are unlikely to disrupt the deeply socialized, effectively branded tradition of the two party vote. On the supply side .. well, these reforms haven’t gained that much traction or funding.

All of this bubble-busting is to tell you that the logic of competition doesn’t work out in the real world as smoothly as it does in a business school case study.