AI, so the story goes, is the paradigm-shifting technology of our time. OpenAI’s CEO recently claimed that ChatGPT now boasts 1 billion active users, roughly 12% of the world’s population.

And yet, there’s a lot of confusion about how the public actually uses or even understands AI. A shocking poll from January claimed that 99% of U.S. adults used an AI-powered product in the past week. Rutger’s National AI Opinion Monitor paints a different picture, reporting last year that 53% of Americans had ever used a generative AI tool, and just over a third have used ChatGPT specifically. Only 12% of adults are even aware of the term “large language model”.

To be clear, different pictures are being partly because of different brushes (AI products are categorically different from AI platforms), but the point here is three-fold: (1) there’s lots of public opinion research on AI out there now, (2) there’s many ways to ask about AI usage and understanding, and (3) the overall picture of “what the public thinks about AI” is messy. That ambiguity, matters tremendously for companies seeking public legitimacy and regulators gauging public support for oversight.

This post is my attempt to pull together a snapshot of the field — a synthesis of what studies show, what's surprising, what's consistent, and where there's disagreement (since is a blog and not a Fact Sheet, some commentary from me thrown in along the way).

AI on AI: How I wrote this

Sidebar: I enlisted AI’s help for this post. Specifically, I used GPT-4o to help review a set of manually curated studies, and paired it with the new Deep Research tool (bearing the risks in mind) to cast a wider net of high-quality public opinion studies. ChatGPT played the the role of research assistant — helping extract statistics, identify patterns in subgroup differences, cross-check timelines — and sometimes co-author, hypothesizing mechanisms for how attitudes might form or diverge.

Lest this whole thing become a snake eating its own tail, I did some verification by hand. You can see the prompts, verification steps, and notes on my process here. TL;DR: it worked pretty well and rarely, if ever, were there any dubious claims being made. Altogether it probably made this post 3x faster to write.

In total, we (ChatJeeps and I) pulled together about 20 main high-quality survey studies from polling organizations and academic researchers. They spanned 2017 through March of this year, were mostly conducted in the US but some in the UK and elsewhere, and including the usual well-known suspects like Pew, YouGov, and my colleagues over at AP-NORC.

Here’s what we found. Starting with a basic fact:

Concerns about AI are rising, but vary by use case.

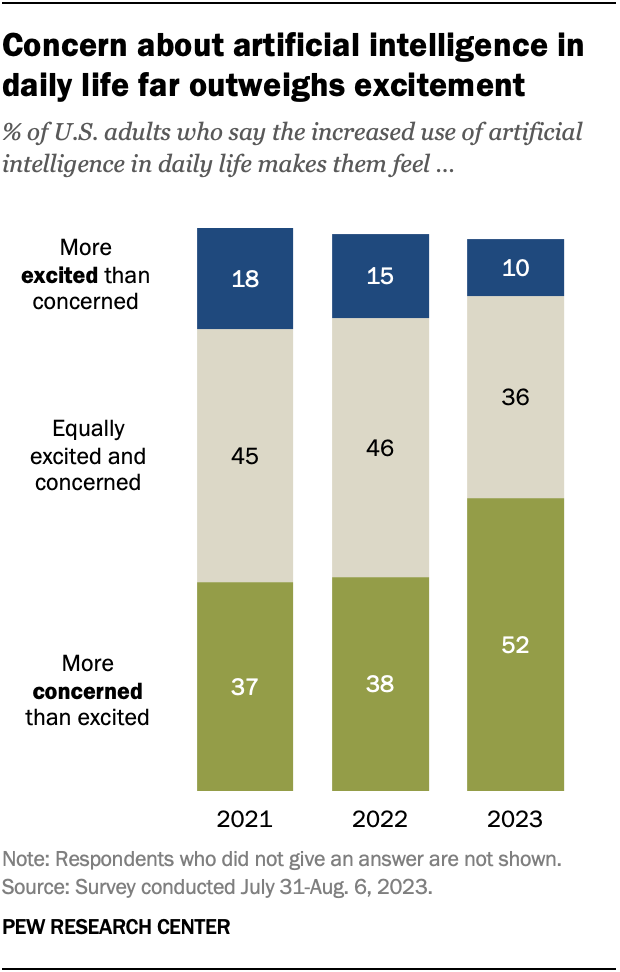

In both the U.S. and UK in recent years, majorities say they feel negative — distrustful, concerned, not optimistic — about AI’s implications for society. Accordingly, support for regulation has risen, with people calling for transparency, human oversight, and limits on automation. This is perhaps best illustrated in Pew’s three waves of AI surveys.

And yet in the same surveys, majorities said AI would be beneficial to society, helpful to them personally, but also risky to democracy and likely to displace workers. You would maybe assume people polarize into “pro-AI” or “anti-AI” camps, but it’s a story of ambivalence, or even cognitive dissonance.

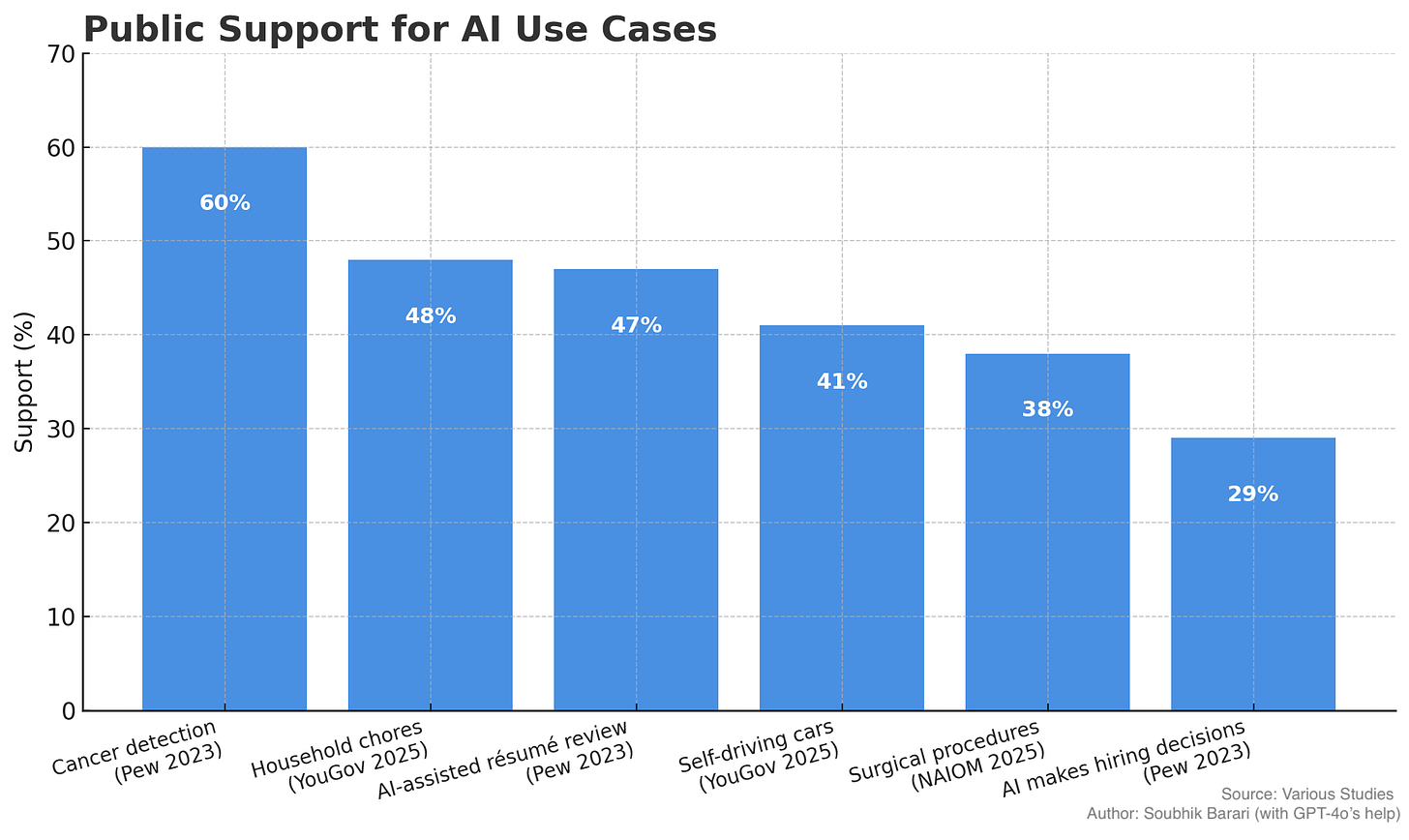

Getting specific about use case is informative. Across surveys where they are asked, people are more comfortable with AI replacing other machines than replacing thinking humans. Comfort drops sharply as AI’s role becomes more autonomous, judgment-based, or higher stakes. A near majority of adults, for instance, disapprove of AI performing surgery, but support the usage of AI for cancer detection. A near majority of adults support AI doing household chores, but not driving their cars. 71% of respondents in one of the Pew studies opposes AI making final hiring decisions, but 47% support AI assisting in reviewing résumés.

Such fears about AI may diverge from past tech anxieties like the fear of nuclear power or early skepticism about the Internet. In those cases, the threat was seen as external: the danger came from how the technology might be misused by bad actors. With AI, by contrast, the unease may center on the technology itself as a rogue agent. This distinction may reflect the way AI has been over-anthropomorphized by developers, media, and academics, in slide decks (guilty) and report cover pages across the globe. The public’s perceived risks are not entirely misguided, but the image of malevolent robots can potentially mislead the public about how these risks play out.

The more you know, the more you trust … maybe?

In most surveys, greater familiarity with AI correlates with more comfort, more use, and more optimism. Across studies, people who report using AI tools regularly or say they understand how they work tend to express higher trust in AI, greater openness to its applications, and less fear about its implications:

Pew (2025) finds that those who report frequent use or high tech literacy are more likely to say AI will be personally helpful.

YouGov (2025) shows that weekly users of generative AI report less concern than infrequent or non-users.

Zhang & Dafoe (2019) noted that computer science training and education level were among the strongest predictors of support for developing AI.

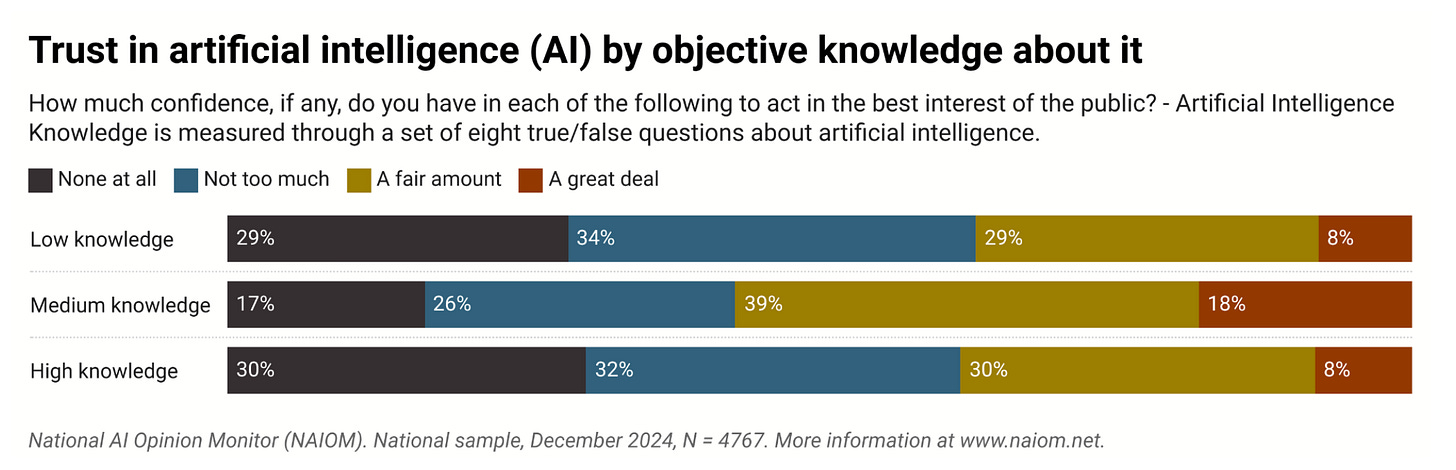

An interesting outlier is the National AI Opinion Monitor (2025) study, which reports a curious twist in the shape of a “U”: trust in AI is highest among people with medium objective knowledge, but drops among those with high or low knowledge.

That begs the question of what kind of knowledge we’re exactly talking about. In NAOIM’s study, “knowledge” was measured via a basic 8-item true/false quiz — questions like whether AI can create music or whether ChatGPT was trained on Wikipedia. But self-reported familiarity with AI terms doesn’t necessarily track real conceptual understanding of how these systems work or their broader societal risks. The fact that so few people know basic terms like “large language model” doesn’t inspire confidence either.

So while greater knowledge of AI generally tracks with higher support, there might also be a tipping point—where deeper understanding shifts people from ‘hey, this is great!’ to a healthy appreciation of the downsides (hallucination, misinformation, etc.).

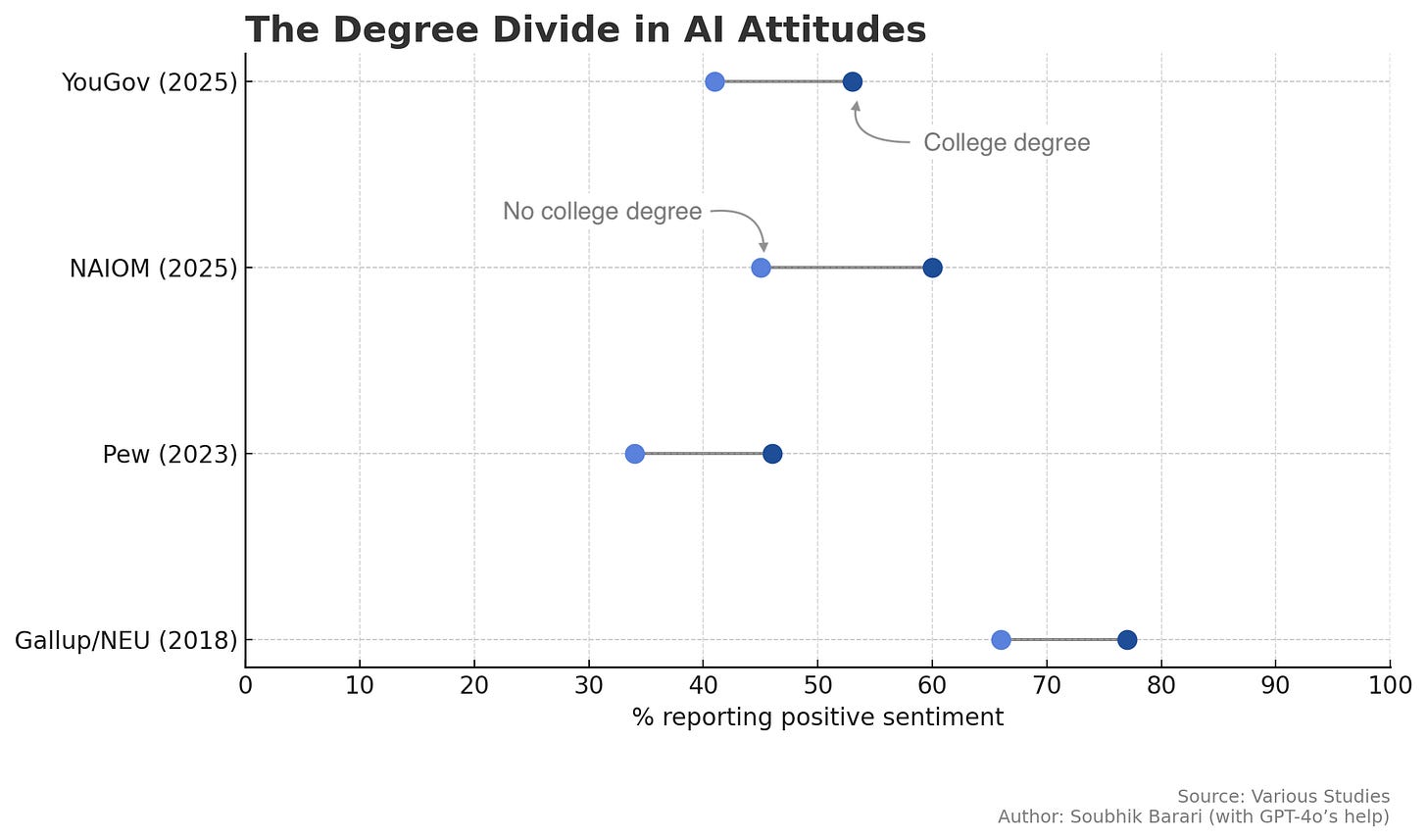

AI attitudes map onto America’s growing diploma divide.

The “diploma divide,” or gap in attitudes between degree and non-degree holders, has emerged as an important fault line in American politics. When it comes to AI, this may offer one of the clearest snapshots of how public opinion is splitting. Across surveys, college-educated respondents are consistently more optimistic about AI, more likely to trust the institutions behind it (60% vs 45% of non-degree holders in NAOIM), and more confident in their ability to understand or use it.

The following subgroups also stand out across multiple studies:

Asian Americans. 62% of Asian American respondents said they trust AI-generated information — the highest score across all racial/ethnic groups, compared to the 48% national average (NAIOM, 2025).

High-Income Individuals (>$100K). 63% of high-income Americans trusted AI to act in the public interest (NAIOM, 2025).

Men. 52% of men expressed confidence in AI, compared to lower rates among women (NAIOM, 2025).

Frequent AI Users. Weekly AI users were more likely to say AI would have a positive societal impact and expressed higher trust in outputs (YouGov, 2025).

Young Adults (18–29 / 25–44). Younger adults were more likely to use AI, see it as personally relevant, and recognize terms like “generative AI” (Pew, 2023; Gov.uk, 2024).

These sociological cleavages may be as much about core psychological dispositions. Agreeableness tends to predict more favorable views of AI, while conspiratorial thinking was associated with greater skepticism.

The public’s perceived impacts of AI are paradoxical.

I do love a good paradox … but like most paradoxes, this is not actually a paradox, only paradoxical. People, as it turns out, are capable of holding multiple, apparently contradictory opinions.

The paradox-y phenomenon here can perhaps be described as disconnected fear and optimism. In the 2018 Northeastern/Gallup study, for instance, three-quarters of respondents said AI would fundamentally change how we live and work in a positive way. And yet, most also believed AI would result in net job losses, also seen in the Pew studies. In Pew (2025), however, only 28% expected AI would significantly affect their own job.

Similarly, several surveys show that older adults (55+) are less likely to say AI will affect them personally, but more likely to express fear — especially about privacy, surveillance, and misinformation. Meanwhile, younger people are more likely to use AI, see it as personally relevant, and are less concerned about its broader impacts.

As always, it’s Complicated™.

There’s a lot more to learn from public opinion data on AI, even from these 20 studies. Still, I would conclude there is some clear directionality in public opinion towards AI. There are some clear divides by education, income, age and meaningful variation by use case. But these divides aren’t always sharp, and public sentiment feels like a mixed portrait, and possibly — unlike with the calcified voting public — malleable and unsettled (lots of very slim majorities!). We might draw out a model of attitude formation that looks like:

direct experience > secondhand factual knowledge > imagination and analogyImagination and analogy can bias the public away from reality and not just with robot fears. People might be also quick to draw the parallels between AI and nuclear power. But as leading AI researchers have pointed out, this might be a faulty comparison since the discovery of a fully autonomous superintelligence (unlike the atomic bomb) is not itself the proof of an existential threat.

Public opinion is full of these kinds of contradictions of “disconnected fear and optimism.” Americans say they distrust “Congress” but like their representative; they support government spending cuts broadly, but oppose cuts to specific programs. They say they want more housing, but not in their neighborhood. Some of this is an artifact of survey research. Depending on how questions are framed — broad vs. specific, personal vs. societal, promise vs. peril — people can give very different answers.

And depending on what’s happening in tech news, people might be sincerely thinking different thoughts the next time you ask them about AI. The recent AI 2027 report is a good example—a vivid, falsifiable forecast from a former OpenAI researcher of a dramatic escalation in model improvements is on the horizon which further portends a massive economic disruption and a geopolitical arms race that could upend the global order. Reading about doomsday makes a person reasonably sour on AI. So your belief about AI beliefs (*Zaller 1992 vibrating on bookshelves everywhere*) should probably look more like:

mediated expert opinions > direct experience > secondhand factual knowledge > imagination and analogyAll said, whatever may be causing it, the ground is clearly shifting on AI, but so is the sky. There are many plausible places where they (and we) might all land, even in the near future.

You can attempt to replicate the research for this post yourself using the prompts and specification on the Somewhat Unlikely code repository here.

It sounds like artificial intelligence is still largely under researched by the general public, but in my opinion, AI usage by corporate and state actors have interest in advancing their usage for varying interests. I don’t mind the usage of AI, we as a society will adapt for employment and governing* purposes.

However, the concern of AI being used for resume reviews concerns me about the previously convicted, work gaps, and other things like age, school rankings, etc. I feel like hard cutoffs to such groups would leave behind those who already find employment hard to come by.

My other concern is my biggest fear. “Hallucination” will not be acknowledged as much as it needs to be as acceptance rises of AI, my assumption as time goes on, paired with the risks of over relying on the technology and, the contradictive nature of our views could be taken advantage of and LLMs could be used influence views to shift them a certain way, as pointed out potentially with the twitter/X LLM this year

What accountability happens to those to alter models to fit their narratives(to me fines aren’t enough). What if a LLM is altered to hurt the image of a group or demographic or promote a negative narratives? What if ad generated prompts are introduced, how would small businesses compare to the brand-bias of large business? How do normal citizens and smaller interests get skin the game to counteract the largely invested?

I feel like AI is like one of those pharmaceutical commercials, a prescription for the “narcotizing dysfunction”(your class) caused by the constant flow of information. Something to help stimmy the flow of information by being able to process the world with easy-to-use prompts in LLMs. But the symptoms have yet to fully reveal themselves and aren’t presented well enough to question if they are worth the costs in the context of broad society like how they are in the commercials.